Why Is Academia Liberal?

It's not human capital, and it might not be discrimination either.

Navigation:

-The Stated Views Of The Academy

‒Bias Against Race Science

‒Bias Against Whiteness

-Why Does The Academy Lean So Far Left?

‒Age

‒IQ

‒Conscientiousness, Religiosity, & Grades

‒Openness

‒Education

‒Material Considerations & Self-Selection

‒Political Discrimination

—Direction Of Causality

-References

The Stated Views Of The Academy:

Of the 66 top-ranked liberal arts colleges in the United States, 51 make voter registration information public as of 2017 [16]. Overall, there are 10.4 registered Democrats for every registered Republican among the professors at these institutions, although it varies by college with 20/51 having a percentage-Republican which does not differ significantly from zero [16, p.7]:

In College Pulse’s 2023 Undergraduate Student Panel [61], which includes more than 700,000 students from >1,500 US colleges/universities in all 50 states, 58% of respondents reporting being slightly, somewhat, or very liberal whereas 22% reported being either independent or apolitical and 20% reported being slightly, somewhat, or very conservative. Conservatives reported being significantly-less comfortable voicing their views on controversial subjects [61, p.5]:

Although 70% of students reported being somewhat or very comfortable expressing their views, 47% of these respondents answered this way for the reason that their views aligned with the people around them [61, p.6]:

This was the reasoning of most liberal-leaning students but was not the case for conservative-leaning students [61, p.6]:

Only 35% of students answer that controversial speakers should have their invitations withdrawn if students disagree with their views, but this view is at near parity among liberal-leaning students [61, p.12]:

The same is also true regarding whether reading requirements should be dropped if they make students feel uncomfortable [61, p.14]:

Regarding whether professors should be reported for making statements that students find offensive, conservatives were split roughly evenly on the issue while liberals expressed much more substantial support for professors being reported [61, p.16]:

When questioned on whether students should be reported for making offensive statements, the difference was much more stark [61, p.21]:

Bias Against Race Science:

Arguably, the difference is understated due to conservatives and liberals having different things in mind when asked the question, with conservatives perhaps thinking more of things like insults while liberals are maybe more likely to have political opinions or empirical assertions in mind; respondents were asked whether professors should be reported for 10 specific statements [61, p.17]:

Liberal students had roughly the same responses regarding whether a professor should be reported for expressing at least one of these views, but among conservatives, opposition rose to 59% [61, p.20] from the 47% it was at in figure 24:

Conservative students’ answers didn’t vary much on issue whereas liberals were much more supportive of professors being reported for the set of statements they disagreed with [61, p.19]:

Overall, students were most supportive of reporting professors who contest the presence of anti-Black bias in police shootings [61, p.18]:

In the FIRE Scholars Under Fire data [57] regarding 537 incidents targeting a scholar for some form of professional sanction over constitutionally protected speech between 2015 and 2021, more than half (328 in 537; 61%) of the incidents were initiated by groups or individuals who leaned leftward relative to their target [57, p.25] while just over a third (193 in 537; 36%) were initiated by groups or individuals who leaned rightward, and in this minority of cases, university administrators were 2.625 times as likely (21% versus 8%) to support the target [57, p.22]. 44.9% (241 of 537 incidents) of targeted scholars expressed something about race whereas 24.4% (131 of 537 incidents) expressed partisan political views and 23.1% (124 of 537 incidents) expressed views about institutional policy [57, p.24]. In a subset of 19,969 students from 55 universities recruited for the FIRE 2020 College Free Speech Survey and drawn from College Pulse’s American College Student Panel™, speakers arguing that some racial groups are less intelligent than others were the ones that students were most opposed to being allowed to speak at university campuses [58, p.19]:

In the 2021 FIRE College Free Speech Survey of 37,104 students from 159 US colleges and universities drawn from College Pulse’s American College Student Panel™, racial inequality was the issue students rated as being most difficult to have an honest conversation about [59, p.12]:

Of the issues where responses differed significantly by political orientation, conservatives consistently reported having the greatest difficulty [59, p.13]:

In a series of five surveys [29, pp.20-32] of university staff and Ph.Ds in the social sciences and humanities, respondents were asked the following [29, pp.20-21]:

“If a staff member in your institution did research showing that greater ethnic diversity leads to increased societal tension and poorer social outcomes, would you support or oppose efforts by students/the administration to let the staff member know that they should find work elsewhere?”

[Support, oppose, neither support nor oppose, don’t know]

“If a staff member in your institution did research showing that the British empire did more good than harm, would you support or oppose efforts by students/the administration to let the staff member know that they should find

work elsewhere? “

[Support, oppose, neither support nor oppose, don’t know]“If a staff member in your institution did research showing that children do better when brought up by two biological parents than by single or adoptive

parents, would you support or oppose efforts by students/the administration to let the staff member know that they should find work elsewhere?

[Support, oppose, neither support nor oppose, don’t know]Please imagine a member of your organization has done work showing that having a higher share of women and ethnic minorities in organizations correlates with reduced organizational performance. Several thousand professionals, some from your organization, have signed an open letter calling for the staff member

to be fired in order to protect disadvantaged groups from a hostile learning environment. A small group have started a counter-petition defending the staff

member on grounds of academic freedom. Would you:

Sign the open letter, which called for the staff member to be fired,

Support the views expressed in the open letter, but choose not to sign it,

Not support nor sign either letter,

Support the counter-petition, but choose not to sign it,

Sign the counter-petition,

Don’t know.

[a question on whether academics would support or oppose firing a member of staff who wants immigration to be reduced.]

The support for at least one cancellation campaign was as follows [29, p.24]:

Across samples, left-wing political views emerged as one of the primary predictors of supporting at least one cancellation campaign, second only to age [29, p.31]:

Across samples, nearly half of the youngest respondents supported at least one cancellation campaign [29, p.32]:

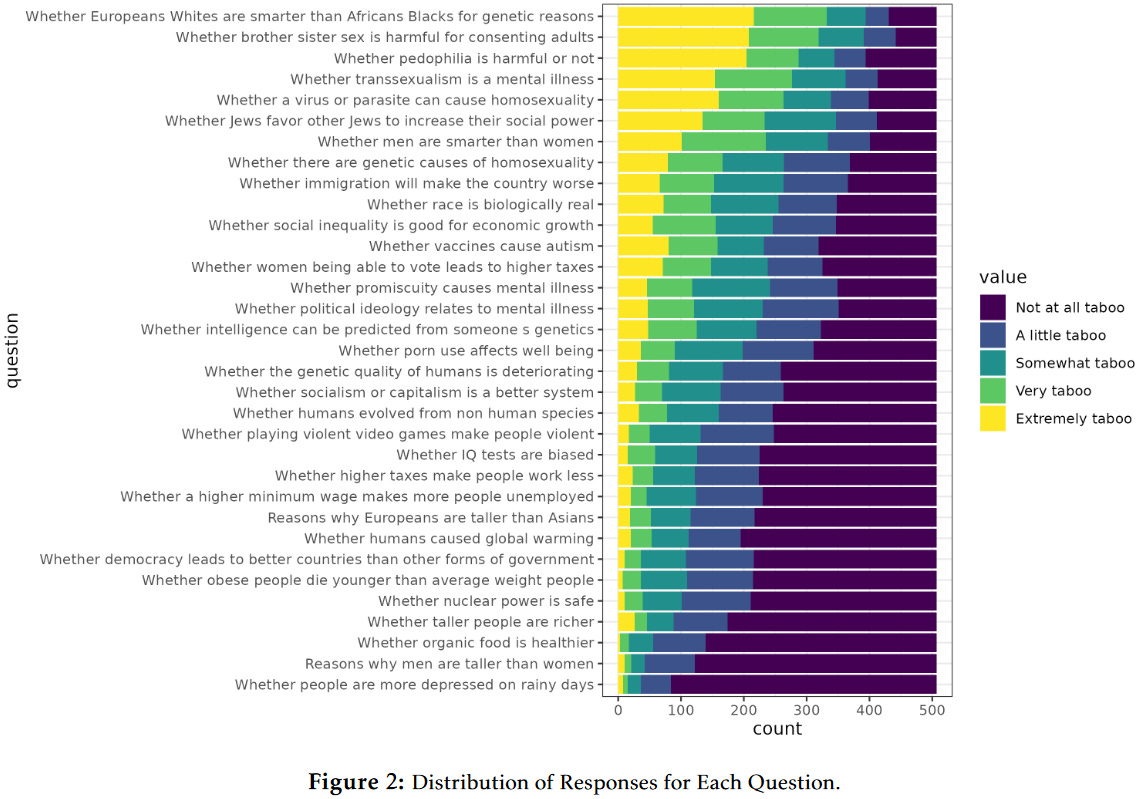

In the most extensive list of topics that’s been evaluated, average Americans view the question of genetic differences in intelligence between Africans and Europeans as being even more taboo than the question of whether or not pedophilia is harmful, whether or not incest is harmful, and whether or not Jews favor other Jews to increase Jewish social power [60, p.6]:

Bias Against Whiteness:

None of this should be too much of a surprise since across cultures, the lowest common denominator of what people associate with the political terms "right" and "left" is the acceptance or non-acceptance of inequality [62 & 67]. Then again, this probably isn’t completely sufficient to explain the bias against race science since leftists also have a robust anti-White bias across contexts:

[68] In these two experiments, liberals were more willing to sacrifice a White person for the greater good than a Black person:

In the first experiment, 88 students from the University of California were introduced to the classic philosophical trolley problem where they had the choice of letting a train run over a crowd of 100 people, or intervening by killing a single person in order to prevent this. Participants were randomly assigned to one of two groups:

Group A had the choice of killing “Chip Ellsworth III” to save 100 members of the Harlem Jazz Orchetra.

Group B had the choice of killing “Tyrone Payton” to save 100 members of the New York Philharmonic Orchesta.

After hearing about the scenario, participants were asked the following five 1-7 likert-scale questions which were formed into an α = 0.78 composite:

“Is sacrificing Chip/Tyrone to save the 100 members of the Harlem Jazz Orchestra/New York Philharmonic justified or unjustified?”

(1 = completely unjustified, 7 = completely justified)“Is sacrificing Chip/Tyrone to save the 100 members of the Harlem Jazz Orchestra/New York Philharmonic moral or immoral?”

(1 = extremely immoral, 7 = extremely moral)“It is sometimes necessary to allow the death of an innocent person in order to save a larger number of innocent people.”

(1 = completely disagree, 7 = completely agree)“We should never violate certain core principles, such as the principle of not killing innocent others, even if in the end the net result is better.” (reverse coded; 1 = completely disagree, 7 = completely agree)

“It is sometimes necessary to allow the death of a small number of innocents in order to promote a greater good.”

(1 = completely disagree, 7 = completely agree)

Participants were generally more willing to sacrifice Chip than they were to sacrifice Tyrone (β = −0.19, t = 2.24, p = 0.03). There was a significant scenario X liberalism interaction effect (β = 0.20, t = 2.26, p = 0.03), with liberals being significantly more likely to sacrifice Chip (β = −0.40, t = 3.27, p = 0.002) while conservatives had no detectable bias (β = 0.01, t = 0.09, p = 0.93).

In the second experiment, 96 Cornell University students and 80 random Californian adults repeated the scenario except with either Chip or Tyrone being thrown off a lifeboat in order to prevent it from sinking and killing 100 generic occupants. Participants were given the following four 1-7 likert-scale items so as to produce an α = 0.75 composite:

“Is sacrificing Chip/Tyrone to save the other members on board acceptable or unacceptable?”

“Is sacrificing Chip/Tyrone to save the other members on board moral or immoral?”

“We should never violate certain core principles, such as the principle of not killing innocent others, even if in the end the net result is better.”

“It is sometimes necessary to allow the death of innocents lives in order to promote a greater good.”

This time, the overall sample didn’t have a significant average bias, but there was once again a significant (β = 0.12, t = 2.15, p = 0.03) scenario X liberalism interaction effect with liberals being significantly (β = −0.19, t = 2.43, p = 0.02) more willing to sacrifice Chip while conservatives did not significantly vary their decisions across scenarios (β = 0.05, SE = .08, t = 0.61, p = 0.54).

[64] In this experiment conducted on 1,057 university students (128 from a British university, 480 from a Hungarian university, and 449 from Prolific Academic in the USA), participants were randomly presented one of two otherwise-identical passages from a fictional book:

“Scholars have suggested that white people score higher than black people on intelligence tests. It is likely that at least some of this gap is caused by genetics. That is, whites are genetically smarter than blacks.”

Pg. 64“Scholars have suggested that black people score higher than white people on intelligence tests. It is likely that at least some of this gap is caused by genetics. That is, blacks are genetically smarter than whites.”

Pg.64

Participants then rated their 1-7 likert-scale agreement with four statements:

“They should remove the book from the library.”

“A professor should not be allowed to require the book for class.”

“Students should not be allowed to cite the book.”

“It would not be good if students read the book.”

Responses to the four items were then aggregated into an α > 0.93 composite measuring overall support for censorship. Support for censorship rose by 2 standard deviations among left-leaning participants in the case where the passage was anti-Black instead of anti-White (β = 2.04, t = 12.26, one-tailed p < 10^-35). Conservatives had a similar bias which was in the same direction but to a smaller degree (β = 1.34, t = 8.04, p < 10^-16). A passage X conservatism interaction term did not have a significant effect, but there’s a highly-preferable test the authors could have done to formally assess whether liberals and conservatives differed in biases: Assuming the t values (12.26 & 8.04) of these two effects are equal to the ratios of effect sizes to standard errors, we can divide the betas by the t values to get standard errors of 0.1664 & 0.1667, thereby allowing the standard error of the difference in effects to be calculated as being √(0.1664 ^ 2 + 0.1667 ^ 2) = 0.236, and so dividing (2.04 - 1.34) / 0.235 yields a t value of 2.979, which yields a one-tailed p value of 0.00145.

This assumption is probably correct seeing as the ratio between t values is nearly the same as the ratio between effect sizes, only the conservative t value is very slightly smaller as we’d expect from the very-slightly liberal leaning nature of the sample.

In similar experiments comparing statements about the violence of Islam and of Christianity and about the leadership ability of men and of women, the authors also found a p < 0.05 passage X conservatism interaction effect in the case of religion, and replicating previous research [65], found a p < 0.001 passage X conservatism interaction effect in the case of sex. A non-academic sample in the paper also found significant interaction effects in all three cases; p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001 in the sex, race, and religion experiments respectively [64, p.15].

[66] Across a series of 6 experiments (combined N = 2,519), liberals repeatedly rated information as being more credible when it portroyed Blacks/women more favorably than Whites/men instead of portraying Whites/men more favorably than Blacks/women [66, p.72]:

[63] In this survey, 1,014 Americans were randomly asked one of four of the following:

“Suppose somebody asserted a generalization which portrays White people negatively. Would this be racist?”

“Suppose somebody asserted a generalization which portrays White people positively. Would this be racist?”

“Suppose somebody asserted a generalization which portrays Black people negatively. Would this be racist?”

“Suppose somebody asserted a generalization which portrays Black people positively. Would this be racist?”

Overall, negative generalizations had twice the odds of being rated as non-racist if Whites were the target (OR = 2.11, p < 0.001). Among self-described anti-racists however, the effect was even larger (OR = 3.279402, p < 0.00001), and the effect was greater still among non-Republicans (OR = 3.76, p < 0.00001).

[69] This paper did two experiments finding liberals to feel that Blacks living in fire-prone or otherwise-risky houses shouldn’t pay higher rates of home insurance while feeling neutral as to whether or not Whites should:

In the first experiment, 199 participants were first given one of three scenarios to read:

[race-neutral scenario]

”Dave Johnson is an insurance executive who must make a decision about whether his company will start writing home insurance policies in six different towns in his state. He classifies three of the towns as high risk: 10% of the houses suffer damage from fire or break-ins each year. He classifies the olher three towns as relatively low risk: less that 1% of the houses suffer fire or break-in damage each year.”['anti-Black' scenario]

”Dave Johnson is an insurance executive who must make a decision about whether his company will start writing home insurance policies in six different towns in his state. He classifies three of the towns as high risk: 10% of the houses suffer damage from fire or break-ins each year. It turns out that 85% of the population of these towns is Black. He classifies the olher three towns as relatively low risk: less that 1% of the houses suffer fire or break-in damage each year. It turns out that 85% of the population of these towns is White.”['anti-White' scenario]

”Dave Johnson is an insurance executive who must make a decision about whether his company will start writing home insurance policies in six different towns in his state. He classifies three of the towns as high risk: 10% of the houses suffer damage from fire or break-ins each year. It turns out that 85% of the population of these towns is White. He classifies the olher three towns as relatively low risk: less that 1% of the houses suffer fire or break-in damage each year. It turns out that 85% of the population of these towns is Black.”

Respondents then declared their level of agreement with five 1-9 likert-scale items, which were later formed into an α = 0.78 composite:

The executive should offer insurance policies for sale in all of the towns and for the same price across all of the towns.

The executive should offer insurance policies for sale in all six towns but charge higher premiums for people who live in the high-risk towns.

The executive should feel free to offer insurance policies for sale only where he feels he can make a reasonable profit, and if that means only selling policies in the low-risk towns, so be it.

If the executive won't write policies for all of the towns, he should write policies for none of the towns.

If the executive offers insurance policies for sale only in the low-risk towns, the government should have the right to prosecute him and his company for its discriminatory behavior.

Moderates and conservatives didn’t vary across conditions, but compared with the racially-neutral condition, liberals became significantly-more egalitarian when told that the poor people were Black whereas there was no effect of being told that the poor people were White [69, p.862]:

With the race-neutral and 'anti-White' scenarios combined into a single group, the liberal-conservative difference in egalitarianism was significantly smaller than in the 'anti-Black' scenario (one-tailed p = 0.00000354).

In the second experiment, 330 participants were given a scenario where the following was explained (paraphrasing):

'Because of the aging state of many houses in Columbus, and because of the steep increase in the use of electrical appliances in modern society, the threat of fire to homes is at the greatest level in years. Because of this increased threat, mortgage lenders require all home owners to obtain fire insurance. For an insurance company to make a profit, rates must be set so as to cover the predicted amount of money lost from fires in a specific risk category. Houses can be classified into three categories of neighborhood risk for fire damage: a 1 in 1,000; a 1 in 500; and a 1 in 100 chance of fire damage or loss per year. Accountants have compiled a table that insurance agents can use in setting insurance premiums: The company would need to sell policies for an average of $100 in the low-risk neighborhood; $200 in the medium-risk neighborhood; and $1,000 in the high-risk neighborhood. These premiums would permit the company to profit sufficiently in each zone. To profit sufficiently while charging the same rate across all neighborhoods, the company would have to charge $430.'

Participants were told to imagine that they were a representative of the company who had discretion about which pricing scheme to offer a homeowner from a high-risk zone. Participants were then asked: "Based on the information your accountants have given you about the applicant's neighborhood, how much would you charge for this person's insurance policy?" A subset of the participants were then told that 10% of the population of the low-risk zone was Black while 30% of the medium-risk zone was Black and 70% of the high-risk zone was Black. From there, this subset was asked if they would like to revise their offer, and if so, what they’d like to change it to. Liberals were significantly more likely to revise their initial offerings (one-tailed p < 0.000000407), and liberalism correlated significantly with the magnitudes of their revisions (β = +0.49, p < 0.001). Participants assigned to this subset were then compared to—a control group which did not receive the information about racial disparities—on their responses to three 1-9 ‘moral cleansing’ likert-scale items that were asked of both groups:

the emphasis participants planned to put (relative to last year) on attending organized cultural activities such as an African American art show;

the interest expressed in participating in a campus-wide rally for racial equality;

the interest expressed in participating in an organized publicity drive to locate a student who had mysteriously disappeared.

On a composite of the three items, liberals in the experimental group declared significantly-higher 'moral cleansing' intentions (sum-score mean = 13.8) than liberals in the control group (sum-score mean = 10.6); one-tailed p = 0.000011).

[70] Since ~2005, White liberals have been the only demographic to report more warmth towards other racial groups than towards their own [70, pp.102-104]:

[71] This experiment asked respondents to rate the fairness of hiring discrimination in different scenarios with different targets and where certain scenarios had utilitarian justifications available. Overall, respondents rated discrimination against Blacks as being more unfair than discrimination against Whites [71, p.46]:

Whites viewed anti-White discrimination neutrally while Blacks viewed it favorably [71, p.47]:

Liberals view anti-Black discrimination as being particularly unfair while conservatives regard both scenarios favorably and to an approximately-equal degree [71, p.48]:

Overall, conservatives viewed utilitarian-based discrimination favorably while viewing non-utilitarian discrimination neutrally. By contrast, liberals viewed utilitarian discrimination neutrally while viewing non-utilitarian discrimination unfavorably [71, p.48]:

[72] Across a series of 6 experiments (combined N = 4,545), participants repeatedly required that Whites meet higher standards on admissions criteria than what they required for admitting Blacks to an honor society; conservatives displayed the same bias as liberals but merely to a smaller degree [72, p.29]:

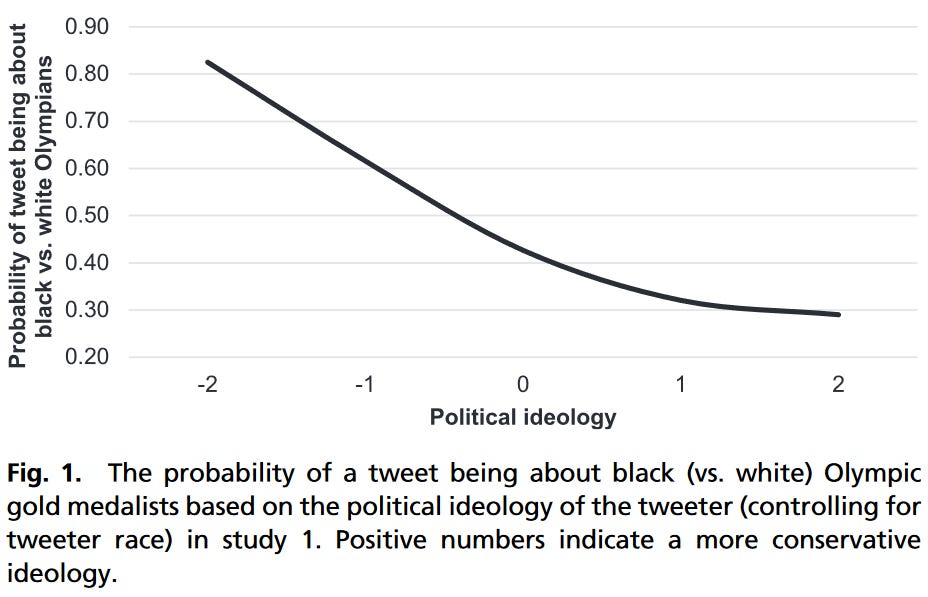

[73] In a sample of >500,000 tweets from >160,000 twitter users regarding 46 gold medalists from the 2016 Olympics, liberals were found to be more likely than conservatives to celebrate the victories of non-White athletes relative to their celebration of the victories of White athletes [73, p.3]:

The authors later verified the effect experimentally. In one experiment regarding which scientific experts a sample of 788 (393 Democrats & 395 Republicans) participants would connect with media outlets, the more-conserative participants were not more likely (i.e. 33% by chance versus 38%, 95% CI = [31%, 45%]) to select a Black+female expert meanwhile the more-liberal ones were more likely than chance (i.e. 33% by chance versus 47%, 95% CI = [40%, 54%]) to select the Black+female expert.

This isn’t technically the correct way to conduct this statistical test however; a non-overlapping confidence interval strictly guarantees significance, but at the same time, an overlapping confidence interval doesn’t guarantee non-significance. We can subtract the lower intervals from the upper intervals and divide these differences by 1.96 to get standard errors of (45-31)/(2*1.96) = 3.571 and (54-40)/(2*1.96) = 3.571. Dividing 33/3.571 gives us a z score of 9.2411 in the null case, whereas 38/3.571 = 10.6413 and 47/3.571 = 13.1616; from there, subtracting 10.6413- 9.2411 = 1.4002 and 13.1616 - 9.2411 = 3.9205, these z scores yield one-tailed p values of 0.0807 and 0.00004418272 respectively. With there being a standard error of √(2 * 3.571 ^ 2) = 5.050157 for the difference in percentages, dividing (47-38)/5.050157 = 1.782123 yields a one-tailed p value of 0.037; here we have weak evidence that the conservatives displayed less of an anti-White bias than the liberals did.

When the authors analyzed political views with a continuous measure however (which is the better way of testing for differences), greater liberalism did significantly predict selecting the Black+female athlete (β = −0.24, p = 0.003).

Why Does The Academy Lean So Far Left?

It hasn’t always been this way. A 1969 Carnegie Commission survey [17] found that 28% of American university faculty were conservative while 27% were centrists and and 45% were left/liberal: a left:right ratio below 2:1, and in the sciences, a left:right ratio of 1:1. By contrast, later 1984 Carnegie data showed that just 39% of faculty were left/liberal, and the conservative share had risen to 34% [18], a balance approaching 1:1, which led Hamilton & Hargens to state that “the incidence of leftism [among faculty] has been considerably exaggerated.” Then, in 1989 & 1997, the Carnegie data showed a leftward shirt back towards a 2:1 ratio, which was confirmed by the 1989 and 2001 HERI studies [19], with the ratio among the professoriate growing further to 3.5:1 by the mid 2000s [20] and the growth only continuing to the 10.4:1 ratio [16] of the present day. Similar shifts since the 1990s have occurred in Great Britain [29, pp.68-70] whereas the American trend over the same time period was as follows [29, p.67]:

The shift among faculty is also partially reflected in the student body. The Higher Education Research Institute of UCLA runs something it calls the Cooperative Institutional Research Program which samples representative samples of college freshmen every year, totaling 10,100,596 students and 1,240 institutions over the course of the program’s history [36, p.321]; since 1982, liberalism among college freshmen immediately began growing at the expense of the center while conservatism remained stagnant rather than declining [36, data on pp.83-85]:

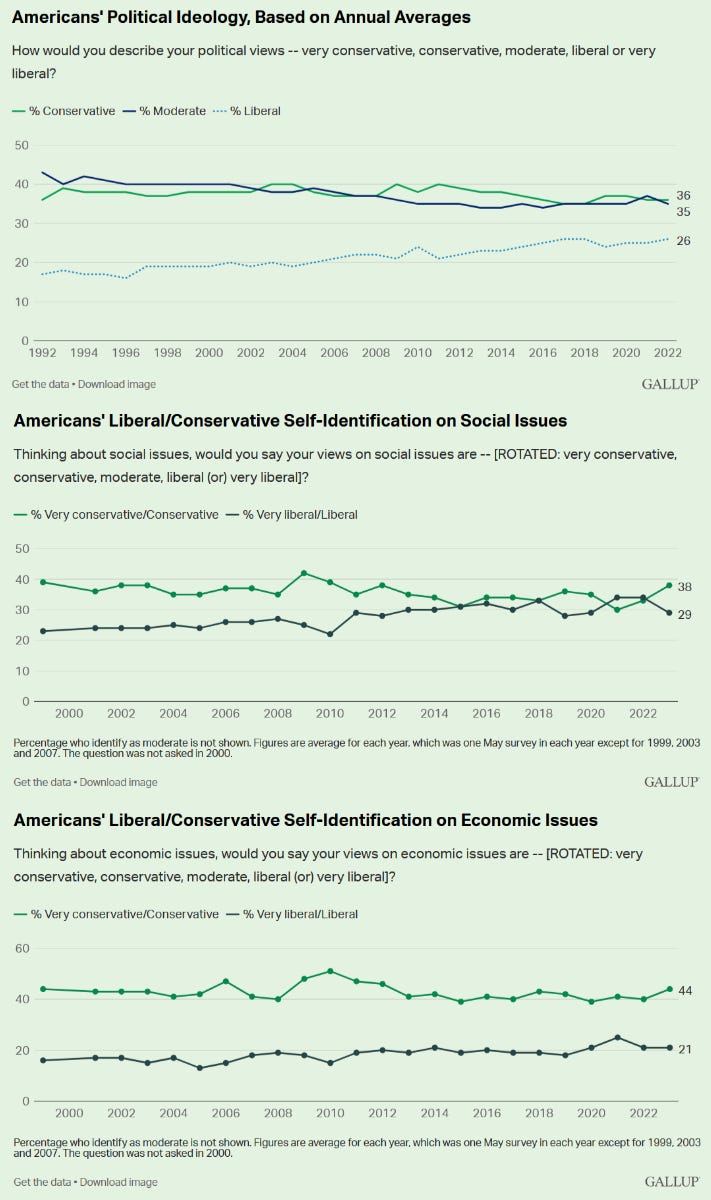

Conservatism hasn’t declined like it has among university faculty, but there has been a decline in the conservative:liberal ratio due to an increase in liberalism. It’s worth remembering that neither the trends among faculty or among the student body can be explained by general shifts in ideological identification among the general population since the growth in liberalism within academia precedes the population-level growth since 1995, in addition to conservatism among academic faculty experiencing a decline reflected by neither the student body nor the general population. Across several longitudinal samples I managed to track down, the general American population continued skewing increasingly conservative until ~1995:

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1ruNTtU8x6qICCSAR2QWeat6HItgcZUoEUHgUk0Zwa8Q

not-equal.org/content/publicationSupplements/Trends_in_conservatism.xlsx

1992-2022 Gallup data retrieved from reference 37, 2023 Gallup entries based on regressions of Gallup’s political conservatism data on Gallup’s data on social and economic conservatism data [using 37 & 38]. Gallup, CPS, and SRC ratio data from before 1992 taken from the line graph of reference 39 using the https://plotdigitizer.com/ tool. Kaiser Family Foundation data taken from reference 40. ANES [42] and GSS [41] data accessed directly, using the ANES ‘VCF0004’, ‘VCF0803’, & ‘VCF0009z’ variables, and the GSS ‘polviews’ variable:

https://gssdataexplorer.norc.org/trends?category=Politics&measure=polviews_r

https://electionstudies.org/data-center/2020-time-series-study/

Once again however, putting the trend in terms of the conservatism:liberalism ratio obscures that conservatism has been approximately constant since the early 1980s, with change in the ratio reflecting rising liberalism rather than declining conservatism. Here are the trends within the GSS data [41]:

Here are the trends within the Gallup data [37 & 38]:

The ANES data is a bit of an outlier in showing a growth in both liberalism and conservatism at the expense of the center [42]:

Finally, here’s what the very-limited KFF data looks like [40]:

Age:

There is a well-replicated age-conservatism correlation [46], and in the GSS, ANES, & Gallup data, young adults self identify as roughly 5% to 10% less conservative and as 5% to 10% more liberal. We have a good idea what drives the age-conservatism correlation. There exists a mountain [46] of evidence that parenthood is causal for conservatism:

Longitudinally, parents become more conservative when they have children.

Experimentally reminding people of their parenthood status causes them to identify as more conservative.

Across hundreds of enormous (total N = 426,444), nationally-representative samples from the world values survey (and in previous research as well as the authors’ own 10-nation sample) conducted across four decades and 88 nations, parenthood consistently explains the age-conservatism correlation:

Replicating the previous research from American samples, the authors’ original 10-nation survey found that the β = +0.34 association of age with social conservatism became a non-significant β = −0.07 [−0.32, 0.19], p = 0.605 effect when controlling for binary parenthood status.

Across all WVS waves (total N = 426,444), the β = +0.04 association between age and sexual conservatism reversed to a β = -0.27 (p < 10 ^ -40) effect when controlling for parenthood and a β = -0.53 (p < 10 ^ -149) effect when controlling for number of children.

In the WVS wave 5 & 6 samples (N = 173,540), the β = +0.50 association of age with traditionalism declined to a β = +0.14 effect when controlling for binary parenthood status and reversed to a negative β = −0.15 (one-tailed p = 0.000538) effect when controlling for number of children.

In the WVS wave 6 & 7 samples (N = 167,677), ingroup preference (i.e. trust in foreigners and in members of alien religions subtracted from trust in family and neighbors) did not correlate with age β = 0.00, 95% CI = [−0.03, 0.03], and controlling for parenthood created a negative β = -0.15 (p < 0.0001) effect while controlling for number of children created a negative β = -0.33 (p < 0.0001) effect.

As a tangent, the fact that parenthood is causal for conservatism is reason not to bank on ‘outbreeding liberals’ being reason to expect a conservative victory. Not necessarily that a strategy of outbreeding liberals couldn’t be effective in theory (The A^2 (~40%) & C^2 (~18%) effects [47] are high enough), but conservatism would have to actually be causal for fertility in order for an average fertility differential to matter, and so if a causal effect of conservatism on fertility doesn’t exist right now, it would have to be created/strengthened in order for it to be reason to be expect increases in conservatism over time. Then again, the fact that controlling for fertility shifts the age correlation to be negative would be consistent with such an effect already existing.

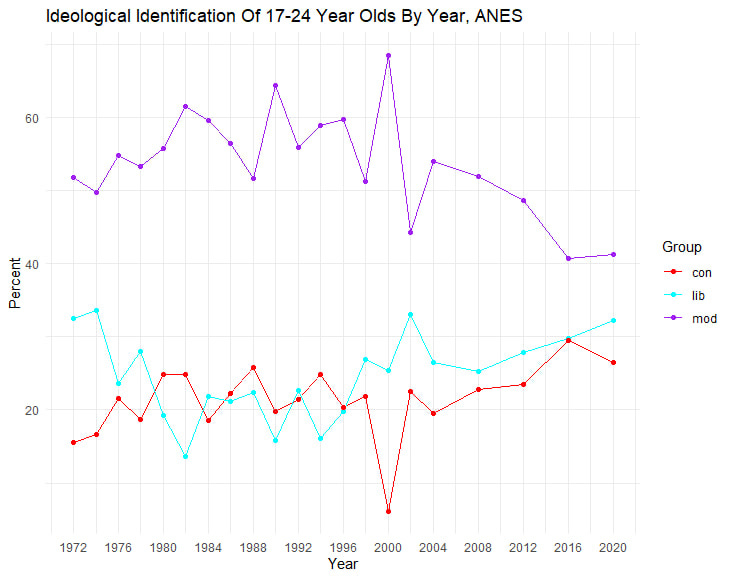

Can the differences between the trends within the CIRP samples and those within the general population be explained by age? Although it seems likely that age would explain why young-adult samples of college students would generally be more liberal than older adults, the fact that controlling for parenthood flips the age-conservatism correlation implies that any cohort effects should be in a conservative-trending direction, and hence trends of increasing liberalism over time should be due to average within-person shifts in opinion over time with it not likely being the case that the trends among young people have diverged from the trends among the general population. Are these priors borne out by the data? When restricted to 17-24 year olds, the ANES trends are as follows:

Variables: Age = VCF0101, Ideology = VCF0803, Year = VCF0004, sampling weights = VCF0009z

It seems that a conservative:liberal parity stays steady until that familiar year of 1996 at which point the liberals began growing. Clearly, the skew among college freshmen began before the skew among the general population.

Do note that at n = 68, the sample size for the year 2000 is abnormally low compared to other years and that the conservative dip is likely just a matter of random sampling error.

Gallup puts the departure from parity even later; in the 18-29 cohort, it was only in ~2013 that liberals began growing at the expense of conservatives, and only among women that this occurred [45]:

Age isn’t broken down as well in the GSS, but for the 18-34 bracket, liberals actually seem generally stable until 2012, but there’s a decline in the conservative:liberal ratio around 1996 due to a decline in conservatism [41]:

All told, none of our datasets give us any reason to think that the early-1980s divergence of college freshmen from the rest of the population has anything to do with age trends.

IQ:

Why has the skew become so extreme since the early 1980s? Is it that conservative ideas have just lost in the marketplace of ideas with it only being stupid people who still believe in them? While there is a well-established gap in intelligence between liberals and conservatives, the difference is only a small one, with a meta-analysis finding only 4% of variance in political views to be attributable to intelligence [21]. Moreover, the correlation between intelligence and leftism has only been declining over time; the meta-analysis doesn’t pick this up in its moderator analyses due to artificially discretization into three time periods and due to considering attitudes and prejudice separately, but when we ameliorate these problems, there is an r = -0.175 correlation between publication year and absolute effect size with a one-tailed p-value of 0.046. Furthermore, there is an r = -0.45 correlation between standard error and publication year, and when weighing by squared reciprocal standard errors (using wtd.cor() from the weights package [27] in R), there was an r = -0.25 correlation between absolute effect size and publication year with a one-tailed p-value of 0.00862. Doing a more-proper meta regression with the metafor package [48], z = 1.75, p < 0.05. Over the same period of time, academia has also been becoming much less selective in terms of intelligence; although the correlation between IQ and educational attainment has not been declining [22], the average IQ of university students has been declining [23]. If the left:right ratio among the professoriate were a matter of intelligence, this would only be reason to expect a decline in the left:right ratio as opposed to the increase that we’ve observed. Moreover, the shift also applies to the subset of right-wing views which are positively correlated with intelligence (e.g. economic conservatism), hence political views in academia have come to be skewed in proportion to how left wing they are rather than how they correlate with intelligence [28].

There’s also no guarantee that causality would go from the IQ distribution to the demographics of universities instead of the other way around. While the gains are hollow for g, there is a well-established causal effect of educational attainment on nominal IQ scores [24], and so we might posit part of the IQ-leftism correlation to be explained by a hostile university environment pushing conservatives out. From this we might speculate that IQ differences between Democrats and Republicans would be inflated by 'test bias' and also that the gap would be smaller among older adults than it is among younger adults.

Conscientiousness, Religiosity, & Grades:

A reason we might predict conservatism to be overrepresented in academia if we didn’t know any better is that it correlates at r = +0.10 with conscientiousness [35]. Interestingly enough, despite correlating negatively with IQ [32 & 33] and possibly being the ‘active ingredient’ in the IQ-leftism correlation, religious commitment correlates at r = +0.31 with academic achievement/GPA in the USA and at r = +0.19 in Europe [34].

Note that the meta-analyses [32 & 33] on religiosity and IQ find null correlations between religiosity and GPA, but they are each much smaller (k < 10) than the meta-analysis of academic achievement and religious commitment (k = 88) [34]. By contrast, the k=88 alternative [34] conflates academic achievement and GPA a bit with behavioral problems, but this isn’t likely to explain the disagreement given that the association with educational outcomes doesn’t differ much from purer measures of behavioral outcomes. It would be great if the commitment-achievement meta-analysis [34] was done with greater clarity, but the meta-analyses on intelligence [32 & 33] are likely a severely-restricted selection of the evidence on GPA given that educational outcomes weren’t the point of focus in the literature search, which was literally for (IQ OR intelligence OR “cognitive ability”) AND (religious OR religiosity OR “religious beliefs” OR spirituality) [32]. In any case, even null results for GPA are a problem for a human capital explanation of academic demographics.

Regarding conservatism specifically, in a sample of 7,207 students in the HERI dataset from 156 campuses [79], conservatives had higher grades in high school meanwhile conservatives reported worse relationships with college faculty and had lower grades in college even controlling for SAT scores, SES, and demographics. This may not be too much of a surprise given that 7%-15% of academics state that they would mark down term papers from right-leaning students [29, p.170] and that stated willingness to discriminate rises by a factor of 2 to 3.2 under conditions of anonymity [29, p.139].

Openness:

Do conservatives take less interest in education because they don’t hold to the academic values of curiosity and open mindedness? There exists a difference, but it is incredibly small and it has been decreasing linearly over time. In a meta-analysis [78] of over 200,000 participants from 341 samples collected between 1948 and 2019, the overall effect is r = +0.155, with only 2.4025% of variance in conservatism being attributable to differences in openness. The decline was also concentrated on the association of openness with social conservatism, with an effect of r ~= +0.246 in 1948 and declining to r ~= +0.153. Like intelligence, openness is actually something of an anti-explanation for why conservatives have become so underrepresented in academia.

Education:

Does learning neutral information while spending time in academia cause initially politically neutral samples to adopt left-wing views? While there are within-person effects, longitudinal studies find that political socialization in college is a function of one’s peers rather than educational achievement tout court [25 & 26]. When the same cohorts of students at freshman year are followed up with years later, the CIRP studies [25] found overall leftward shifts in the 1966 cohort, overall rightward shifts in the 1971 cohort, and polarized shifts away from the center in the 1983 and 1987 cohorts [25, p.406]:

In a similar 2020 study [26] at Cornell University and the University of Michigan, a minuscule but statistically significant rightward shift also occurred. By contrast, controlling for their initial views, students end up correlating nearly as much with their cohort’s average freshman-year views (i.e. ‘peer normative context’) as they do with their initial views, regardless of whether the school leans right or left [25, p.407]:

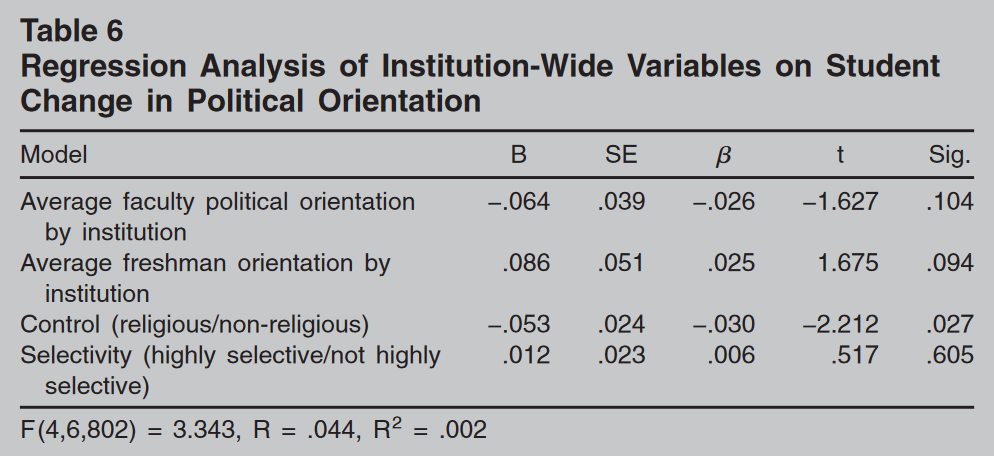

In another follow-up CIRP study [44] of 6,807 students from 38 private colleges in 2003, it was also found that further-left leaning universities were not more likely to have students shift leftwards from their freshman-year views, albeit in this cohort there was a small overall leftward shift compared to students’ initial political views:

In the Michigan-University study [26] again, students assigned to random roommates ended up significantly (p < 0.001) more similar in political views during the follow-up wave than during their initial meeting a year earlier. By contrast, students don’t seem to move towards their professors’ views [43]:

While the results this paper [43] presents on page 348 aren’t the greatest reason to come to this conclusion, the way it does its analysis can be improved upon to give a stronger result. For those students who had Democrat, independent, and Republican professors for a class, the effect sizes and confidence intervals for students’ shifts away from the GOP were β = 0.06 +/- 0.04, β = 0.03 +/- 0.08, and β = 0.07 +/- 0.10 respectively; thereby implying standard errors of 0.0204, 0.0408, and 0.051 respectively when lower intervals are subtracted from upper intervals and the differences are divided by (2*1.96). Weighing the latter two effects by squared reciprocal standard errors yields an estimated β = 0.0456, SE = 0.0319 effect size among the 424 students with non-democrat professors, thereby yielding a non-significant (p = 0.352) difference of 0.0144 between the changes in views experienced by these students and the 1,117 students whose professors were Democrats; although we cannot say that the students with non-Democrat professors shifted significantly away from the GOP, the non-significant shift away from the GOP that they experienced did not differ significantly from the shift experienced by students whose professors were Democrats. In any case, even among the students whose professors were Democrats, what little significant shift students had away from the GOP was practically minimal.

Further evidence which strengthens this view comes from an attempt [90] to see what happens to the political views of students who have extra contact with faculty more generally. Since, as we’ve seen, professors are very liberal, such students should presumably experience a greater peer-contagion effect. As it happens, such students tend to become more moderate rather than more liberal; conservative students became more liberal while liberal students became more conservative [90, pp.146-148]:

Thus far, we’ve only seen information about the effects of university attendance on ideological identification, but we also have some evidence [88, p.76] from the 1999 North American Academic Study Survey (NAASS) shedding some light on how college students’ views change on specific issues over time rather than asking about broad ideological identification. We see no effects aside from a slight increase in acceptance towards homosexuality, and a decline in support for government wealth redistribution:

Notably, there were no effects on racial views, patriotism, environmentalism, Christian sexual morality, freedom vs equality preference, or party identification.

Finally, another follow-up CIRP study [89] of 17,667 students who attended 156 campuses in 2009 and 2013 broke from the prior couple of surveys in finding a bit of an overall leftward shift; the mean leftist student moved 0.27 units to the right on a 1-5 likert scale whereas the mean centrist drifted 0.13 units leftward and the mean right-wing student moved 0.48 units to the left [89, pp.2-3]:

This was further reflected on polling of specific issues. Although there was little shift in views on whether racism was a serious problem in the United States, respondents shifted significantly leftward in their views on affirmative action, gay marriage, and abortion [89, pp.4-5]:

Contrary to the contextualizing notes however, we already know from the GSS, Gallup, ANES, and CIRP data that the conservatism:liberalism ratio was on the decline in the general population during the relevant timeframe, so it isn’t clear that the effects found here can be entirely attributed to colleges causing students to shift leftwards in ways that normal people were not.

Material Considerations & Self-Selection:

In a 2020 survey of 843 Masters and Ph.D students on Prolific Academic [29, p.91], participants were asked “How interested are you in pursuing a career as a university academic (i.e. Lecturer, Professor)?” on a 5-point scale ranging from “not at all interested” to “extremely interested” and then asked which of the following affect their decisions:

“Academic jobs are too hard to get, especially where you want them.”

“I can earn more money in a different job.”

“Academia is too isolating, I prefer more social interaction at work”

“There is too much form-filling and hoop-jumping in academia”

“My political views wouldn’t fit, which could make my life difficult.”

“I’m not the academic type.”

Political views did not correlate significantly with interest in an academic career, with right-wing views positively predicting it if anything [29, p.94]:

Right-wing political views didn’t significantly predict any of the justifications aside from negatively correlating with “Academic jobs are too hard to get, especially where you want them” and positively predicting “My political views wouldn’t fit, which could make my life difficult” [29, p.93]:

The latter consideration increases considerably as respondents’ listed political views go from “very left” to “very right” [29, p.92]:

One explanation [29, p.92] put forward is that conservatives place greater priority than liberals on having children. Although there has been an intensifying difference in fertility [83, ch.5], freshmen in the CIRP data [36, pp.83-85] have increasingly been rating “having a family” to be an “essential” or “very important” objective while still attending college anyways, and so it doesn’t seem clear that this should translate to a demographic shift in either direction:

Discrimination:

When surveyed, conservatives seem to state that they face a hostile political climate in academia [29, pp.107-111], but is this merely a way of coping with their underrepresentation in intellectual spaces? Revealed preference is that conservatives do what would be rational if they were correct; they have a tendency to try to camouflage their ideological views so as to avoid attracting attention. For one, the academic fields with the lowest conservative underrepresentation are consistently the STEM fields [16, p.5; & 29, pp.97-107]:

Since these are the most rigorous fields [75], this is the opposite of what one should predict if conservative underrepresentation were a human capital problem, but it is what one should predict from the social sciences and humanities making one’s political views so visible within their work [29, pp.66 & 177]. Another good sign of this being the case is that anonymous surveys [76] of political views in academia find more republicans; comparing the ratios found under anonymous conditions to ratios of fields from the figure above, anonymity seems to divide the Democrat:Republican ratio by about 1.5:

A third sign is that conservative perceptions of a hostile climate against conservatives dissappear when controlling for personal experiences with a hostile political climate. In a survey [74] of 292 members of the APA Society for Personality and Social Psychology, respondents were asked how much they felt a hostile climate toward their political beliefs in their field, whether they were reluctant to express their political beliefs to their colleagues for fear of negative consequences, and whether they thought colleagues would actively discriminate against them on the basis of their political beliefs. An α = 0.93 composite of these three 1-7 likert-scale items correlated at r = +0.50 (p < 10^-23) with conservatism, and at r = +0.544 when correcting for the reliabilities of the ideology and experience scales (0.5 / √(0.93 * 0.91) = 0.544). Given the same three questions but with “conservative social–personality psychologists” swapped out as the target, an α = 0.85 composite of the three items correlated with conservatism at r = +0.28 (p = 0.00000123), and at r = +0.318 (0.28 / √(0.85 * 0.91) = 0.318) when corrected for the reliabilities of the scales involved. When personal experience with hostile political climate was controlled for, believing that conservatives face a hostile climate flipped to correlating with conservatism at an insignificant r = -0.01. Respondents were also asked if they would discriminate against conservatives when reviewing a research paper, when reviewing a grant application, deciding to invite somebody to a symposium, or when choosing candidates for a job opening; these responses (1 = Not at all, 4 = Somewhat, 7 = Very much) correlated with liberalism at r = −0.32 (p < .0001), r = −0.34 (p < .0001), r = −0.20 (p < 0.001), and r = −0.44 (p < .0001) respectively.

Finally, among American legal scholars who had donated to Republicans, volunteers could not guess their conservative political leanings from their academic work, but upon reading the work of ones who had donated to Democrats, volunteers could indeed identify their liberal political leanings [77].

Are conservatives rational to camouflage themselves like this? Yes, there are real professional consequences when they reveal themselves [29, pp.13-14 & 136-163]:

Across six samples of academics, the proportion who declare that they would discriminate against right-leaning papers reviews, promotion applications, and grant reviews is as follows [29, p.109]:

Some of the minority of right-leaning academics discriminate against left-leaning academics in these cases, but their influence is roughly offset by left-leaning academics discriminating in favor of other left-leaning academics [29, pp.151-154]. Moreover, in experiments where participants are allowed to anonymously indicate their intentions to discriminate, rates get multiplied by ~2 to 3.2 while having little effect on samples of Ph.D candidates, thereby suggesting that the two groups have a comparable tendency to discriminate against right-leaning papers & grants & promotions while the Ph.D candidates are merely more-honestly biased [29, p.139]:

When considering the proportion who discriminate against right-leaning academics on at least one outcome, the multipliers imply that in the United States, 74% of academics in the social sciences and humanities (SSH) would discriminate against right-leaning academics while 75% would in Canada and 42%-54% would in Great Britain [29, p.157]. Among Ph.D Students in the United States, the empirical figure is 82% [29, p.14]. Worth considering also is that in any sort of peer review with multiple reviewers or in any sort of hiring/promotion decision decided by committee, the binomial probability of at least one member deciding to discriminate grows with the number of people involved. Given a paper being evaluated by least two reviewers plus an editor, the net effect is a 60%-90% chance of a right-leaning paper being rated lower [29, p.153].

Direction Of Causality:

Given demographic parity in 1980, one should only expect the equilibrium to be broken by discrimination if one side discriminates harder than the other. Alas, the evidence [29, pp.142-153; 80; 81; & 82] is mixed on this question, and even if this were something we knew for sure, there would still be a need to explain why the divergence since 1980 was also one among freshman students (who presumably only self select out of college according to acquired experience with the college environment).

References:

Teplitskiy, M., Acuna, D., Elamrani-Raoult, A., Kording, K., & Evans, J. (2018). The Social Structure of Consensus in Scientific Review. Research Policy, 47(9). Retrieved from http://not-equal.org/content/pdf/misc/10.1016-j.respol.2018.06.014.pdf

Sugimoto, C. R., & Cronin, B. (2013). Citation gamesmanship: Testing for evidence of ego bias in peer review. Scientometrics, 95, 851-862. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-012-0845-z

Wilhite, A. W., & Fong, E. A. (2012). Coercive citation in academic publishing. Science, 335(6068), 542-543. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https:/doi.org/10.1126/science.1212540

Ceci, S. J., Peters, D., & Plotkin, J. (1985). Human subjects review, personal values, and the regulation of social science research. American Psychologist, 40(9), 994. Retrieved from https://not-equal.org/content/pdf/misc/Ceci1985.pdf

Mahoney, M. J. (1977). Publication prejudices: An experimental study of confirmatory bias in the peer review system. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 1(2), 161–175. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https:/doi.org/10.1007/BF01173636

Koehler, J. J. (1993). The Influence of Prior Beliefs on Scientific Judgments of Evidence Quality. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 56(1), 28–55. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.1993.1044

Hojat, M., Gonnella, J. S., & Caelleigh, A. S. (2003). Advances in Health Sciences Education, 8(1), 75–96. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022670432373

Abramowitz, S. I., Gomes, B., & Abramowitz, C. V. (1975). Publish or Politic: Referee Bias in Manuscript Review. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 5(3), 187–200. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1975.tb00675.x

Hergovich, A., Schott, R., & Burger, C. (2010). Biased Evaluation of Abstracts Depending on Topic and Conclusion: Further Evidence of a Confirmation Bias Within Scientific Psychology. Current Psychology, 29(3), 188–209. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https:/doi.org/10.1007/s12144-010-9087-5

Goodstein, L. & Brazis, K. (1970). Credibility of psychologists: An empirical study. Psychological Reports, 27(3), 815-838. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1970.27.3.835

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.), Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Retrieved from https://not-equal.org/content/pdf/misc/Cohen1988.pdf

Krems, J. F., & Zierer, C. (1994). Sind Experten gegen kognitive Täuschungen gefeit? Zur Abhängigkeit des confirmation bias von Fachwissen. [Are experts immune to cognitive bias? The dependence of confirmation bias on specialist knowledge]. Zeitschrift für experimentelle und angewandte Psychologie, 41(1). Retrieved from https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1994-87315-001

Ditto, P. H., Liu, B. S., Clark, C. J., Wojcik, S. P., Chen, E. E., Grady, R. H., … Zinger, J. F. (2018). At Least Bias Is Bipartisan: A Meta-Analytic Comparison of Partisan Bias in Liberals and Conservatives. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(2). Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617746796

Ruscio, J. (2008). A probability-based measure of effect size: Robustness to base rates and other factors. Psychological Methods, 13(1), 19-30. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https:/doi.org/10.1037/1082-989x.13.1.19

Fuerst, G. R. (2021). The Post-hoc 4th Review. Human Varieties. Retrieved from https://humanvarieties.org/2021/10/21/the-post-hoc-4th-review/

Langbert, M. (2018). Homogenous: The Political Affiliations of Elite Liberal Arts College Faculty. Academic Questions, 31(2), 186–197. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.se/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12129-018-9700-x

Lipset, S. M., & Ladd,, E. C. (1972). The Politics of American Sociologists. American Journal of Sociology, 78(1), 67–104. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https:/doi.org/10.1086/225296

Hamilton, R. F., & Hargens, L. L. (1993). The politics of the professors: self-identifications, 1969–1984. Social Forces, 71(3), 603-627. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/71.3.603

Klein, D. B., & Stern, C. (2009). By the numbers: the ideological profile of professors. The politically correct university, 15-37. Retrieved from https://www.aei.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/-politically-correct-university_100224248924.pdf

Gross, N., & Simmons, S. (2007, October). The social and political views of American professors. In Working Paper presented at a Harvard University Symposium on Professors and Their Politics (p. 41). Retrieved from https://studentsforacademicfreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/lounsbery_9-25.pdf

Onraet, E., Van Hiel, A., Dhont, K., Hodson, G., Schittekatte, M., & De Pauw, S. (2015). The Association of Cognitive Ability with Right-wing Ideological Attitudes and Prejudice: A Meta-analytic Review. European Journal of Personality, 29(6), 599–621. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2027

Strenze, T. (2007). Intelligence and socioeconomic success: A meta-analytic review of longitudinal research. Intelligence, 35(5), 401–426. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2006.09.004

Uttl, B., Violo, V., & Gibson, L. (2024). Meta-analysis: On average, undergraduate students' intelligence is merely average. ScienceOpen Preprints. Retrieved from https://www.scienceopen.com/hosted-document?doi=10.14293/S2199-1006.1.SOR.2024.0002.v1

Angleson, C. (2022). Learning, Memory, Knowledge, & Intelligence. half-baked thoughts. Retrieved from https://werkat.substack.com/p/learning-memory-knowledge-and-intelligence-14a

Dey, E. L. (1997). Undergraduate political attitudes: Peer influence in changing social contexts. The Journal of Higher Education, 68(4), 398-413. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.1997.11778990

Strother, L., Piston, S., Golberstein, E., Gollust, S. E., & Eisenberg, D. (2020). College roommates have a modest but significant influence on each other’s political ideology. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 202015514. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2015514117

Pasek J., Tahk, A., Culter, G., & Schwemmle. M. (2021). weights: Weighting and Weighted Statistics. R package version 1.0.4,. Retrieved from https://cran.r-project.org/package=weights

Carl, N. (2015). Can intelligence explain the overrepresentation of liberals and leftists in American academia? Intelligence, 53, 181–193. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2015.10.008

Kaufmann, E. (2021). Academic freedom in crisis: Punishment, political discrimination, and self-censorship. Center for the Study of Partisanship and Ideology, 2, 1-195. Retrieved from https://cspicenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/AcademicFreedom.pdf

Perkins, D. N., Farady, M., & Bushey, B. (1991). Everyday reasoning and the roots of intelligence. In D.N. Perkins, M. Farady, & B. Bushey (Eds.), Informal reasoning and education. (pp. 83-105). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Retrieved from http://not-equal.org/content/pdf/misc/Perkins1991.pdf

Perkins, D. N. (1985). Postprimary education has little impact on informal reasoning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 77(5), 562–571. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.77.5.562

Dürlinger, F., & Pietschnig, J. (2022). Meta-analyzing intelligence and religiosity associations: Evidence from the multiverse. Plos one, 17(2), e0262699. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8836311/pdf/pone.0262699.pdf

Zuckerman, M., Silberman, J., & Hall, J. A. (2013). The Relation Between Intelligence and Religiosity. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 17(4), 325–354. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868313497266

Jeynes, W. H. (2004). Comparing the Influence of Religion on Education in the United States and Overseas: A Meta-Analysis. Religion & Education, 31(2), 83–97. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1080/15507394.2004.10012342

Sibley, C. G., Osborne, D., & Duckitt, J. (2012). Personality and political orientation: Meta-analysis and test of a Threat-Constraint Model. Journal of Research in Personality, 46(6), 664–677. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2012.08.002

Eagan, K. (2016). The American freshman: Fifty-year trends, 1966-2015. Higher Education Research Institute, Graduate School of Education & Information Studies, University of California, Los Angeles. Retrieved from https://www.heri.ucla.edu/monographs/50YearTrendsMonograph2016.pdf

Saad, L. (2023). Democrats' Identification as Liberal Now 54%, a New High. Gallup News. Retrieved from https://news.gallup.com/poll/467888/democrats-identification-liberal-new-high.aspx

Jones, J. M. (2023). Social Conservatism in U.S. Highest in About a Decade. Gallup News. Retrieved from https://news.gallup.com/poll/506765/social-conservatism-highest-decade.aspx

ROBINSON, J. P., & FLEISHMAN, J. A. (1984). Ideological Trends in American Public Opinion. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 472(1), 50–60. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716284472001005

Enten, H. (2015). There Are More Liberals, But Not Fewer Conservatives. FiveThirtyEight. Retrieved from https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/there-are-more-liberals-but-not-fewer-conservatives/

Davern, Michael; Bautista, Rene; Freese, Jeremy; Herd, Pamela; and Morgan, Stephen L.; General Social Survey 1972-2024. [Machine-readable data file]. Principal Investigator, Michael Davern; Co-Principal Investigators, Rene Bautista, Jeremy Freese, Pamela Herd, and Stephen L. Morgan. Sponsored by National Science Foundation. NORC ed. Chicago: NORC, 2024: NORC at the University of Chicago [producer and distributor]. Data accessed from the GSS Data Explorer website at https://gssdataexplorer.norc.org/trends?category=Politics&measure=polviews_r

American National Election Studies. 2021. ANES 2020 Time Series Study Full Release [dataset and documentation]. February 10, 2022 version. Retrieved from https://electionstudies.org/data-center/2020-time-series-study/

Woessner, M., & Kelly-Woessner, A. (2009). I Think My Professor is a Democrat: Considering Whether Students Recognize and React to Faculty Politics. PS: Political Science & Politics, 42(02), 343–352. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096509090453

Mariani, M. D., & Hewitt, G. J. (2008). Indoctrination U.? Faculty ideology and changes in student political orientation. PS: Political Science & Politics, 41(4), 773-783. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096508081031

Saad, L. (2024). U.S. Women Have Become More Liberal; Men Mostly Stable. Gallup News. Retrieved from https://news.gallup.com/poll/609914/women-become-liberal-men-mostly-stable.aspx

Kerry, N., Al-Shawaf, L., Barbato, M., Batres, C., Blake, K. R., Cha, Y., ... & Murray, D. R. (2022). Experimental and cross-cultural evidence that parenthood and parental care motives increase social conservatism. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 289(1982), 20220978. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9449478/pdf/rspb.2022.0978.pdf

Angleson, C. (2024). How Heritable Are Political Views? Taking The Twin Literature Seriously. half-baked thoughts. Retrieved from https://werkat.substack.com/p/how-heritable-are-political-views

Viechtbauer, W., & Viechtbauer, M. W. (2015). Package ‘metafor’. The Comprehensive R Archive Network. Package ‘metafor’. Retrieved from http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/metafor/metafor.pdf

Bornmann, L., Mutz, R., & Daniel, H.-D. (2010). A Reliability-Generalization Study of Journal Peer Reviews: A Multilevel Meta-Analysis of Inter-Rater Reliability and Its Determinants. PLoS ONE, 5(12), e14331. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0014331

Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric Theory Third Edition. McGraw-Hill Inc. ISBN-10:007047849X. Retrieved from http://not-equal.org/content/pdf/misc/Nunnally1994.pdf

Bradley, J. V. (1981). Pernicious publication practices. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society, 18(1), 31–34. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03333562

Emerson, G. B., Warme, W. J., Wolf, F. M., Heckman, J. D., Brand, R. A., & Leopold, S. S. (2010). Testing for the Presence of Positive-Outcome Bias in Peer Review. Archives of Internal Medicine, 170(21). Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2010.406

Fang, F. C., Steen, R. G., & Casadevall, A. (2012). Misconduct accounts for the majority of retracted scientific publications. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(42), 17028–17033. doi:10.1073/pnas.1212247109 Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1212247109

Steen, R. G. (2010). Retractions in the scientific literature: do authors deliberately commit research fraud? Journal of Medical Ethics, 37(2), 113–117. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.2010.038125

Fang, F. C., & Casadevall, A. (2011). Retracted Science and the Retraction Index. Infection and Immunity, 79(10), 3855–3859. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1128/IAI.05661-11

Brembs, B. (2018). Prestigious Science Journals Struggle to Reach Even Average Reliability. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 12. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2018.00037

German, K. & Stevens, S.T. (2022). Scholars under fire: 2021

year in review. The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression. Retrieved from https://www.thefire.org/sites/default/files/2022/03/02150546/Scholars-Under-Fire-2021-year-in-review_Final.pdf

Stevens, S., & Schwictenberg, A. (2020). College Free Speech Rankings: What’s the climate for free speech on America’s college campuses. The Foundation for Individual Rights in Education. Retrieved from https://not-equal.org/content/pdf/misc/Stevens2021.pdf

Stevens, S., & Schwictenberg, A. (2021). College Free Speech Rankings: What’s the climate for free speech on America’s college campuses. The Foundation for Individual Rights in Education. Available online at: https://www.thefire.org/sites/default/files/2021/09/24110044/2021-CFSR-Report-v2.pdf

Pesta, B., Kirkegaard, E. O. W., & Bronski, J. (2024). Is Research on the Genetics of Race / IQ Gaps “Mythically Taboo?”, OpenPsych. Retrieved from https://openpsych.net/files/papers/Pesta_2024a.pdf

Bitzan, J. (2023). 2023 American College Student Freedom, Progress And Flourishing Survey. NSDU. Retrieved from https://www.ndsu.edu/fileadmin/challeyinstitute/Research_Briefs/American_College_Student_Freedom_Progress_and_Flourishing_Survey_2023.pdf

Lindqvist, J., & DORNSCHNEIDER‐ELKINK, J. A. (2024). A political Esperanto, or false friends? Left and right in different political contexts. European Journal of Political Research, 63(2), 729-749. Retrieved from https://not-equal.org/content/pdf/misc/Lindqvist2024.pdf

Angleson, C. (2024). “Anti-Racist” = Anti-White. half-baked thoughts. Retrieved from https://werkat.substack.com/p/anti-racist-anti-white

Cory Clark, Bo M Winegard, Dorottya Farkas. (2024). Support for Campus Censorship. Qeios. Retrieved from https://www.qeios.com/read/CMVJP3.2/pdf

Stewart-Williams, S., Thomas, A., Blackburn, J. D., & Chan, C. Y. M. (2019). Reactions to male-favoring vs. female-favoring sex differences: A preregistered experiment. British Journal of Psychology, 112(2). Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12463

Winegard, B. M. (2018). Equalitarianism: A Source of Liberal Bias (Doctoral dissertation, The Florida State University). Retrieved from https://gwern.net/doc/sociology/2018-winegard.pdf

Jost, J. T., Glaser, J., Kruglanski, A. W., & Sulloway, F. J. (2003). Political Conservatism as Motivated Social Cognition. Psychological Bulletin, 129(3), 339-375. Retrieved from https://gspp.berkeley.edu/assets/uploads/research/pdf/jost.glaser.political-conservatism-as-motivated-social-cog.pdf

Uhlmann, E. L., Pizarro, D. A., Tannenbaum, D., & Ditto, P. H. (2009). The motivated use of moral principles. Judgment and Decision making, 4(6), 479-491. Retrieved from https://www.sas.upenn.edu/~baron/journal/9616/jdm9616.pdf

Tetlock, P. E., Kristel, O. V., Elson, S. B., Green, M. C., & Lerner, J. S. (2000). The psychology of the unthinkable: taboo trade-offs, forbidden base rates, and heretical counterfactuals. Journal of personality and social psychology, 78(5), 853. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.78.5.853

Goldberg, Z. (2022). Explaining Shifts in White Racial Liberalism: The Role of Collective Moral Emotions and Media Effects. Retrieved from https://not-equal.org/content/pdf/misc/Goldberg2022.pdf

Kuhn, P. J., & Osaki, T. T. (2022). When is Discrimination Unfair? National Bureau of Economic Research (No. w30236). Retrieved from https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w30236/w30236.pdf

Axt, J. R., Ebersole, C. R., & Nosek, B. A. (2016). An unintentional, robust, and replicable pro-Black bias in social judgment. Social Cognition, 34(1), 1-39. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2016.34.1.1

Kteily, N. S., Rocklage, M. D., McClanahan, K., & Ho, A. K. (2019). Political ideology shapes the amplification of the accomplishments of disadvantaged vs. advantaged group members. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(5), 1559-1568. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1818545116

Inbar, Y., & Lammers, J. (2012). Political Diversity in Social and Personality Psychology. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7(5), 496–503. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691612448792

Kirkegaard, E. (2022). IQ's by university major from SAT's. Just Emil Kirkegaard Things. Retrieved from https://www.emilkirkegaard.com/p/iqs-by-university-degrees-from-sats

Klein, D., & Stern, C. (2004). How Politically Diverse Are the Social Sciences and Humanities? Survey Evidence from Six Fields (No. 53). The Ratio Institute. Retrieved from https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/7088884.pdf

Chilton, A. S., & Posner, E. A. (2015). An empirical study of political bias in legal scholarship. The Journal of Legal Studies, 44(2), 277-314. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1086/684302

Acosta, J., & Kemmelmeier, M. (2022). The changing association between political ideology and closed-mindedness: Left and right have become more alike. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 10(2), 657-675. Retrieved from http://not-equal.org/content/pdf/misc/10.5964.jspp.6751.pdf

Woessner, M., Maranto, R., & Thompson, A. (2019). Is Collegiate Political Correctness Fake News? Relationships between Grades and Ideology. EDRE Working Paper No. 2019-15. Retrieved from https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/215464412.pdf

Honeycutt, N., & Freberg, L. (2016). The Liberal and Conservative Experience Across Academic Disciplines. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 8(2), 115–123. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550616667617

Peters, U., Honeycutt, N., De Block, A., & Jussim, L. (2020). Ideological diversity, hostility, and discrimination in philosophy. Philosophical Psychology, 33(4), 511-548. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1080/09515089.2020.1743257

Hanania, R. (2021). Why Is Everything Liberal? Richard Hanania’s Newsletter. Retrieved from https://www.richardhanania.com/p/why-is-everything-liberal

Dutton, E., & Rayner-Hilles, J. O. A. (2022). The past is a future country: The coming conservative demographic revolution (Vol. 76). Andrews UK Limited. Retrieved from https://not-equal.org/content/pdf/misc/Dutton2022.pdf

Van Ophuysen, S. (2006). Vergleich diagnostischer Entscheidungen von Novizen und Experten am Beispiel der Schullaufbahnempfehlung. Zeitschrift für Entwicklungspsychologie und Pädagogische Psychologie, 38(4), 154-161. Retrieved from https://econtent.hogrefe.com/doi/epdf/10.1026/0049-8637.38.4.154

Nature. (2019). Nature celebrates the one-page wonders too pithy to last. Nature, 568(7753), 433–433. Retrieved from https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-01233-3

Einstein, A. (1921). A Brief Outline of the Development of the Theory of Relativity. Nature, 106(2677), 782–784. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1038/106782a0

Stapleton, A. (2024). 100 Top Journals In The World: Ranking, High Impact Journals By Impact Factor. Academia Insider. Retrieved from https://academiainsider.com/top-journals-in-the-world/

Rothman, S., Kelly-Woessner, A., & Woessner, M. (2010). The still divided academy: How competing visions of power, politics, and diversity complicate the mission of higher education. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. Retrieved from https://not-equal.org/content/pdf/misc/Rothman2011.pdf

Woessner, M., & Kelly-Woessner, A. (2020). Why college students drift left: The stability of political identity and relative malleability of issue positions among college students. PS: Political Science & Politics, 53(4), 657-664. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096520000396

Gross, N., & Simmons, S. (Eds.). (2014). Professors and their politics. JHU Press. Retrieved from https://not-equal.org/content/pdf/misc/Gross2014.pdf

Great read.

Just wanted to point out a typo: Across samples, nearly half of the youngest respondents supported at least one cancellation "campagin"

Otherwise though very insightful.

https://x.com/davidshor/status/1838935308722753977 Does your article talk about this (sorry I have not read it yet)