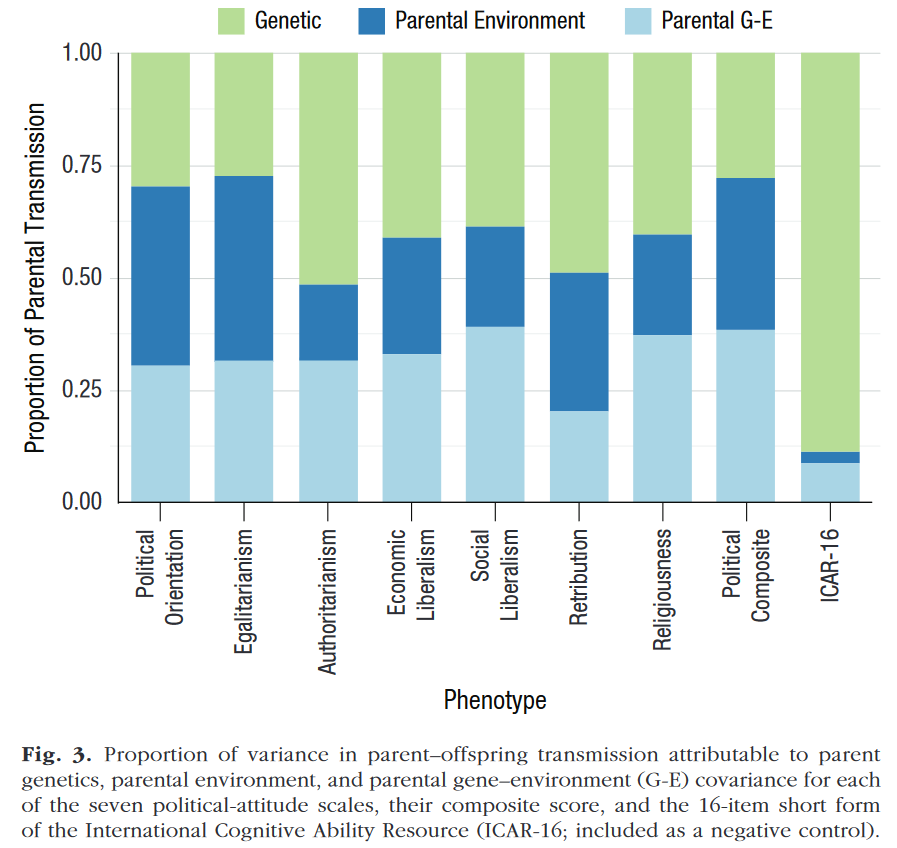

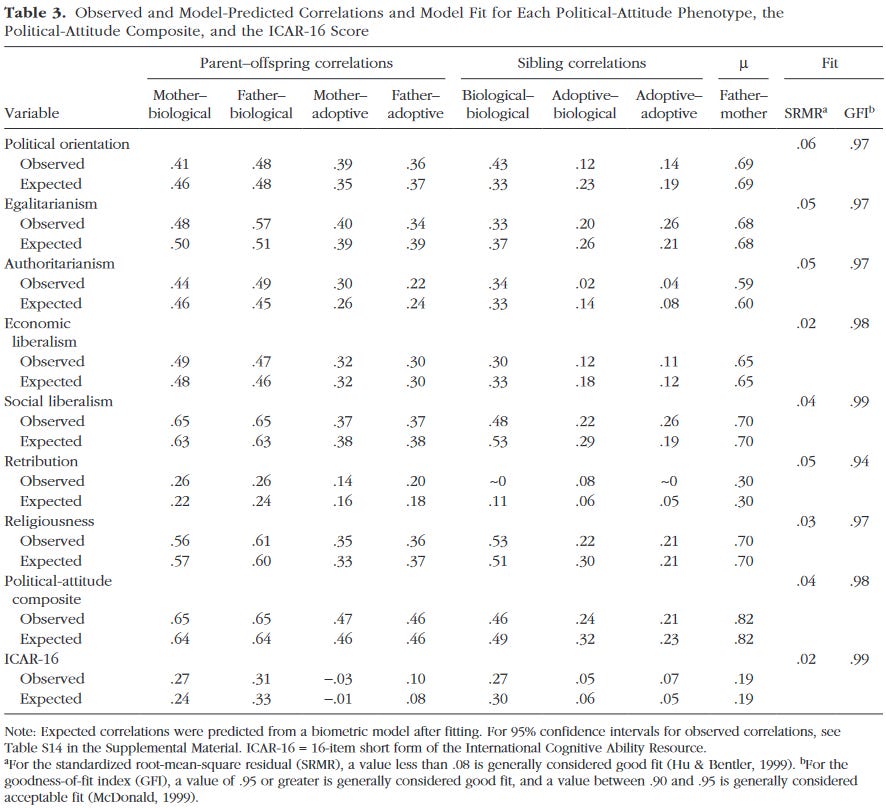

Cremieux recently posted a new adoption study regarding the heritability of political views that I wasn’t aware of [1]. The paper’s official results are as follows:

These results were news to me. It had been a while since I’d gotten into the weeds of the literature on the heritability of political views. I had forgotten most of it, and I was under the impression that political views had a heritability of roughly 60%, with nearly zero shared environment component, and some unknown proportion of the non-shared environment component eaten up by measurement error, with this component being safe to dismiss as random noise, thus leaving the variance worth caring about dominated by the genetic effects. I don’t think I was alone in this assumption. I’d heard statements to this effect from a number of other people. Cremieux himself has even repeated it before [2, citing 3]:

Less interesting to me than the study’s [1]—headline results and custom biometric modelling—are the raw correlations between adoptive and biological siblings:

When deciding what heritability estimates to infer from these results, I hold more trust for the standard formulæ. An adoptive sibling’s shared environment should correlate with their phenotype at C, and should also correlate at C with the phenotypes of other adoptive siblings, thus leaving the phenotypic correlation between separate adoptive siblings at C^2 by transitivity. In addition to the C^2 shared environment effect, a biological sibling’s genotype should correlate with their phenotype at H, two biological siblings should have a kinship coefficient of 0.5, and a counterpart sibling’s phenotype should also correlate at H with their genotype, thus leaving the phenotypic correlation between biological siblings at C^2 + 0.5H^2. As such, with the correlation between biological siblings denoted as rB and the correlation between adoptive siblings denoted as rA, heritability (H^2) can be calculated as 2(rB - rA), shared environment variance (C^2) can simply be calculated as rA, and non-shared environment variance can be calculated as 1 - 2rB - rA:

H^2 = 2(rB - rA)

C^2 = rA

E^2 = 1 - H^2 - C^2 = 1 - 2rB - rA

At least, this is what the formulæ would be if measurement error were counted as an effect of the non-shared environment. If we had a measure of reliability (i.e. percent of variance in observed scores not due to error) denoted as α, we can calculate the proportion of truescore variance caused by differences in genotype as 2(rB - rA)/α, we can calculate the proportion of truescore variance caused by differences in shared environment as rA/α, and we can calculate the proportion of truescore variance caused by differences in non-shared environment as 1 - (2rB - rA)/α:

H^2 = 2(rB - rA)/α

C^2 = rA/α

E^2 = 1 - H^2 - C^2 = 1 - (2rB - rA)/α

The best phenotype variable for political views that the study measures is its ‘political-attitudes composite’, defined roughly as what’s common among the study’s other 6 dimensions of political views, these being ‘anti-Egalitarianism’, ‘Authoritarianism’, ‘Economic Conservatism’, ‘Social Conservatism’, ‘Retribution’, and ‘Religiosity’. No reliability was ever reported for this composite, but reliabilities were reported for the other 6 dimensions, so we can come up with a good guess as to how reliable it might be, taking the other 6 as a floor. The reported reliabilities are as follows:

The mean of the 6 reported α values is 0.84. Of course, a test with 6 times the amount of test content should be more reliable than any given one of its components. How much more? There’s a formula for this! The Spearman-Brown prophesy formula:

rxx’ = n*rxx / (1 + (n - 1)rxx)

where:

rxx is the observed reliability of a reduced-length test

n is the number of parallel forms of the reduced-length test which are included in the full-length test

rxx’ is the reliability to be assumed for the full-length test

Simply substituting rxx = 0.84 and n = 6, we can calculate that rxx’ = 0.96923076923. Finally, we are in a position to calculate our own heritability figures:

Aside from the political-attitudes composite, we’re most interested in the results for the ‘social conservatism’ scale because it has the most content diversity, because it has the second highest among of test content, and because it has the highest correlation with the political attitudes composite while also having a measure of reliability that’s better than the .96 figure we’re assuming for the political composite. Here’s what the questions and item correlations look like in the supplementary materials [4]:

The Twin Literature:

All told, it would seem that for the outcomes most worth caring about (egalitarianism, social conservatism, and the political-attitudes composite) heritability can be properly inferred to explain under 60% of variance, and shared environment effects can be properly inferred to explain over 20% of variance. While the sample is representative, it includes only 370 adoptive siblings and only 310 biological siblings. While powered respectably by the standards of the adoption literature, there’s an entire twin-method literature to look at. How do the results compare? The largest review of studies using the classical twin method finds an N-weighted H^2 figure of 0.4, a C^2 figure of 0.18, and a non-shared environment figure of 0.42 [5, p.6]:

Combined N = 39,304

The statistical power here mostly comes from diverse-content, high item count, Wilson-Patterson type conservatism scales:

Let’s take the 27-item version of the scale as a lowball reliability estimate; this has an α value of .87 [6]. Applying this globally, this would give us a heritability figure of .46, a shared environment figure of .21, and a non-shared environment figure of .33. Clearly, the ‘conventional’ wisdom is wrong. Our measures of political views have always been more reliable than we gave them credit. One’s responses to questionnaires of political attitudes are determined by genotype, non-shared environment, shared environment, and measurement error, in that order, with the sum of the influences of shared and non-shared environments being greater than the influence of genotype.

NOTE: It isn’t entirely clear that it’s fair to describe low internal consistency as being a problem of “measurement error” to be attributed exclusively to non-shared environment. It could just as easily be the result of non-error specificity, which is perfectly liable to have non-zero heritability. Thanks to @tailcalled on twitter pointing this out to me.

Still, it would seem that for the social-conservatism scale in the adoptions study which is most directly comparable to Wilson-Patterson type conservatism scales, the straightforwardly-measured phenotypic correlation between adoptive siblings is a good deal larger than the C^2 estimates inferred by the falconer formulæ of the twin literature. What gives? Maybe the inherent sampling difficulties that come with adoption agencies? Maybe the conservatism scales are worse? Maybe it’s the sample just being smaller? Well, there’s another noticeable difference. In the review of twin studies, all subjects of all samples were over 18 years of age at the very youngest [5]. This makes sense. Adults are the people who vote, and they’re also the people with the most well-formed political views, so those are the kinds of people researchers like to sample. By contrast, the participants of the adoption sample had a mean age of 14.9 years [1, p.3]. As it turns out, the heritability of political views varies widely by age [7]:

While the contribution of non-shared environments remains relatively stable over the lifespan, the shared environment contribution steadily increases up to the age of 17-18 when heritability is under 20% before quickly crashing to the familiar ~20% C^2 effect once kids start moving out of their parents’ homes. This doesn’t only imply extreme malleability, it also goes against the usual pattern for other traits where heritability increases as kids reach puberty (typically happening at 14-15 years of age for boys, and 13-14 years of age for girls).

Ethnocentrism:

As a self-described racist, the heritability of political views is a subject that I care about because I want my continental ancestry group to still be around, genetically speaking, in 1000 years time. The world is currently on schedule for this to not be the case, a development which would be catastrophic and irreversible once the process has been completed. While perhaps not the end of the world, it’s the end of my world, and the only way it’s going to be averted is if people develop the spine to implement the drastic measures that would be necessary to reverse it and to prevent its completion. As such, it is of interest to me to know why certain people seem to care about this issue and others don’t, as well has how to create more of the people who do.

I do not claim by any means that this post is a comprehensive/systemic review of the literature, this is just all of the evidence on the question that I happen to be aware of. To begin, we can look at the VA30K to see how falconer-based heritabilities vary between specific Wilson-Patterson items within a large, public twin sample [8]:

While heritabilities are a bit lower than in most other samples, what we can have more confidence in are the relative within-sample differences; if anything, views on segregation and on forced busing seem to be slightly less heritable than political views generally while views on immigration are about average. This is noteworthy because this is a case where the comparison happens within a particular sample. I’m also aware of estimates from a number of other papers, and while this doesn’t constitute the same kind of within-study comparison, it seems striking to me that this is an issue where heritability figures are lower than they are for political views generally:

References for the table above:

[08] Alford et al. (2005) [11] Truett et al. (1992) [14] Kandler et al. (2014)

[09] Martin et al. (1986) [12] Weber et al. (2011) [15] Orey et al. (2012)

[10] Lewis et al. (2013) [13] Eaves et al. (1989) [16] Bell et al. (2009)

The n-weighted mean heritability estimate for this table is 0.3145.

Ranges given when only sex-specific heritability estimates are available; midpoint estimates used in this case. If a study has multiple phenotypes, within-study averages are used.

EDIT:

Didn’t realize this but Olson & Vernon (2001) has a relevant phenotype:

https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.80.6.845

I’ll synthesize into the table later.

References:

Willoughby, E. A., Giannelis, A., Ludeke, S., Klemmensen, R., Nørgaard, A. S., Iacono, W. G., ... & McGue, M. (2021). Parent contributions to the development of political attitudes in adoptive and biological families. Psychological Science, 32(12), 2023-2034. Retrieved from https://not-equal.org/content/pdf/misc/Willoughby2021.pdf

R, Cremieux. (2023). The Cultural Power of Elite Immigrants. Cremieux Recueil. Retrieved from https://cremieux.xyz/p/the-cultural-power-of-high-skilled/

Hatemi, P. K., Hibbing, J. R., Medland, S. E., Keller, M. C., Alford, J. R., Smith, K. B., … Eaves, L. J. (2010). Not by Twins Alone: Using the Extended Family Design to Investigate Genetic Influence on Political Beliefs. American Journal of Political Science, 54(3), 798–814. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00461.x

Supplementary materials for Willoughby, E. A., Giannelis, A., Ludeke, S., Klemmensen, R., Nørgaard, A. S., Iacono, W. G., ... & McGue, M. (2021). Parent contributions to the development of political attitudes in adoptive and biological families. Psychological Science, 32(12), 2023-2034. Retrieved from https://not-equal.org/content/pdf/misc/10.1177.09567976211021844.supp.pdf

Hatemi, P. K., Medland, S. E., Klemmensen, R., Oskarsson, S., Littvay, L., Dawes, C. T., … Martin, N. G. (2014). Genetic Influences on Political Ideologies: Twin Analyses of 19 Measures of Political Ideologies from Five Democracies and Genome-Wide Findings from Three Populations. Behavior Genetics, 44(3), 282–294. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-014-9648-8

Kalmoe, N. P., & Johnson, M. (2021). Genes, Ideology, and Sophistication. Journal of Experimental Political Science, 9(2), 255-266. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2021.4

Hatemi, P. K., Funk, C. L., Medland, S. E., Maes, H. M., Silberg, J. L., Martin, N. G., & Eaves, L. J. (2009). Genetic and Environmental Transmission of Political Attitudes Over a Life Time. The Journal of Politics, 71(3), 1141–1156. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381609090938

ALFORD, J. R., FUNK, C. L., & HIBBING, J. R. (2005). Are Political Orientations Genetically Transmitted? American Political Science Review, 99(02), 153–167. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055405051579

Martin, N. G., Eaves, L. J., Heath, A. C., Jardine, R., Feingold, L. M., & Eysenck, H. J. (1986). Transmission of social attitudes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 83(12), 4364–4368. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.83.12.4364

Lewis, G. J., Kandler, C., & Riemann, R. (2013). Distinct Heritable Influences Underpin In-Group Love and Out-Group Derogation. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 5(4), 407–413. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https:/doi.org/10.1177/1948550613504967

Truett, K. R., Eaves, L. J., Meyer, J. M., Heath, A. C., & Martin, N. G. (1992). Religion and education as mediators of attitudes: A multivariate analysis. Behavior Genetics, 22(1), 43–62. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01066792

Weber, C., Johnson, M., & Arceneaux, K. (2011). Genetics, Personality, and Group Identity. Social Science Quarterly, 1314–1337. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2011.00820.x

Eaves, L. J., Eysenck, H. J., & Martin, N. G. (1989). Genes, culture and personality: An empirical approach. Academic Press. Retrieved from https://gwern.net/doc/genetics/heritable/1989-eaves-genesculturepersonality.pdf

Kandler, C., Lewis, G. J., Feldhaus, L. H., & Riemann, R. (2014). The Genetic and Environmental Roots of Variance in Negativity toward Foreign Nationals. Behavior Genetics, 45(2), 181–199. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https:/doi.org/10.1007/s10519-014-9700-8

Orey, B. D., & Park, H. (2012). Nature, Nurture, and Ethnocentrism in the Minnesota Twin Study. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 15(01), 71–73. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1375/twin.15.1.71

Bell, E., Schermer, J. A., & Vernon, P. A. (2009). The Origins of Political Attitudes and Behaviours: An Analysis Using Twins. Canadian Journal of Political Science, 42(04), 855. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423909990060

NOTE: It isn’t entirely clear that it’s fair to describe low internal consistency as being a problem of “measurement error” to be attributed exclusively to non-shared environment. It could just as easily be the result of non-error specificity, which is perfectly liable to have non-zero heritability. Thanks to @tailcalled on twitter pointing this out to me.

Crem is female btw https://youtu.be/pmlpggdmeE8?si=RU_-zmEmpffjbeZA