Expert Opinion On Race, IQ, Their Validity, & Their Connection

What do the experts actually believe? How have the experts' views changed? How do the views of elite experts differ from the views of less-elite experts?

What do the experts actually believe? How have the experts’ views changed?

How do the views of elite experts differ from the views of less-elite experts?

This post will go over 4 general topics:

-What do the experts think about g theory and about IQ testing in general?

-How much biological validity to the experts ascribe to racial classification?

-How heritable do the experts think the racial IQ gaps are?

-What do the experts think about other similar topics of interest?

IQ:

Performance on all cognitive tasks positively correlate with performance on every single other cognitive task [1], and under g theory, the existence of a general underlying factor is purported to be the reason for this, and IQ tests are purported to derive utility from being good approximations of this general intelligence factor (g).

The most recent (2020) expert opinion paper [2] only collected a single 1-9 likerts scale item for how much experts endorsed g theory with 9 indicating maximum endorsement; the mean response was 6.84. Non-Ph.Ds were less likely than Ph.Ds to endorse g theory, and publication counts were positively related to endorsement of g theory.

The sample in the study was rather elite. 87% of participants had Ph.Ds, and 60.26% were tenured professors. The average participant had published 94.69 papers (SD = 101.38), with 47.16 (SD = 84.80) of them being on the topic of intelligence. Finally, the median participant had a Harzing h index of 17.A researcher has an h index of n when n is the highest number n such that they’ve published n articles that have each been cited at least n times; the Harzing version, as opposed to the Scopus version, counts works which haven’t been peer-reviewed, such as books or book chapters, and can thus be more readily calculated using Google Scholar).

By contrast, the median Harzing h index of academic neurosurgeons has been estimated to be only 9 [3], with neuroscience professors having a median h-index of 19, and the 95th percentile of neuroscientist h indexes being 36 (we can estimate the 95th percentile of the opinion survey’s h indexes to be approximately 59 given the mean and standard deviation). Differences in raw publication volumes can mean that h indexes aren’t always comparable across fields due to raw publication volumes, but neuroscience researchers are able to get away with publishing far-greater quantities of unreplicable, low-effort, low-n research than psychologists and intelligence researchers [4 & 5]. So, if anything, the gap should be considered to be more profound than if the meaning of h indexes were perfectly comparable across fields.

The response rate (20%) to the survey was however rather low, leaving us with a total sample of only 265 respondents. Should we expect potential differences between survey respondents and non-respondents to bias the results? As Linda Gottfredson noted in her statement [6], “Social and political pressure, both internal and external to the field of intelligence, continues to make scholars reluctant to share their conclusions freely” and over 1/3 of those who declined to sign on to her statement “expressed reasons that signal such reluctance.” Indeed, of those who did respond, more right-leaning researchers—who were more likely to have Ph.Ds, who had published larger volumes of research, and who more strongly endorsed g theory—expressed more hesitation in expressing opinions, rated the field to be portrayed more inaccurately by the media, and more strongly rated it to be increasingly difficult to speak on the matter.This 2008 paper [7] replicated the design of an older 2003 survey [8] of 703 applied psychologists from the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology of the American Psychological Association, but with a more elite sample of researchers who actively contributed to the study of cognitive ability at the time that the survey was conducted. Drawing from the editorial board of the journal Intelligence, the members of the International Society of Intelligence Researchers, and anybody who had published 3 or more articles in the journal of intelligence, 99 unique individuals were identified, 94 of their emails were located, 36 responded to the survey, and 6 responses were excluded because the respondent either lacked a Ph.D, or had published less than 5 papers on the topic of testing or intelligence. Across the board, the more elite sample of experts were more likely to endorse g theory, less likely to think that the tests were biased against minority groups, and thought that IQ had more validity than the less elite sample did. However, for the sample of applied psychologists too, the mean responses should give pause to anybody who thinks that the expert consensus endorses the opposite conclusions. Likert scales of 1-5 were collected with responses of 5 denoting maximum agreement with each statement, mean Likert responses are given under the M columns:

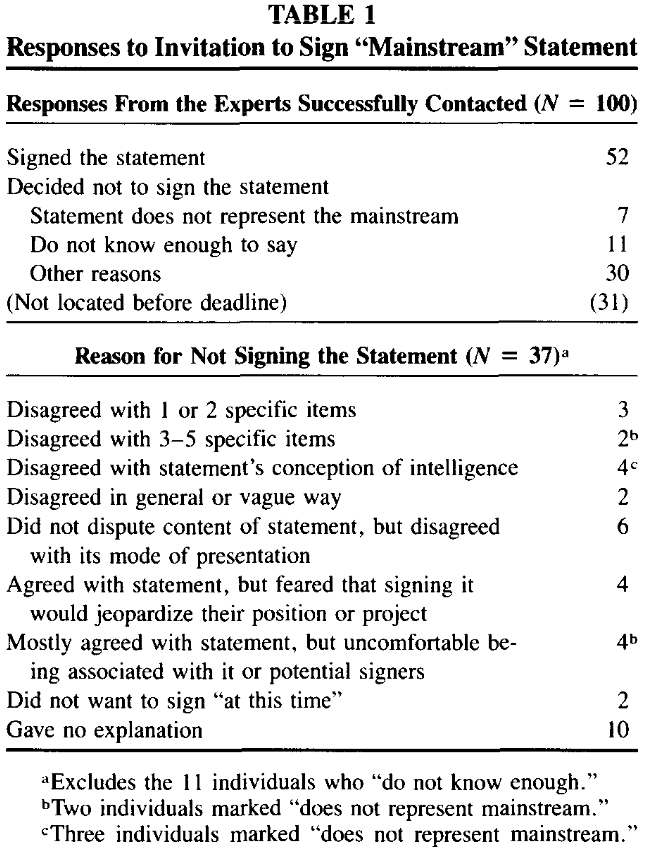

Following the publication of The Bell Curve in 1994 and the controversy that followed, Linda Gottfredson wrote her editorial Mainstream Science on Intelligence [6]. Her aims in writing it, as she describes it “was to gather a large group of highly knowledgeable researchers who represented a wide spectrum of disciplines and perspectives in the scientific study of intelligence. Names were obtained from four sources: (1) lists of individuals elected as fellows (for their distinguished contributions to psychology) by relevant divisions of the American Psychological Association such as educational psychology; school psychology; industrial and organizational psychology; and evaluation, measurement, and statistics; (2) lists of editorial board members of Intelligence; (3) tables of contents of books and journals devoted to the science of intelligence; and (4) suggestions from other people more knowledgeable than I am about some of the subdisciplines in the study of intelligence.” She wrote a 25-point statement she thought could be broadly agreed upon as representing the mainstream findings of the field, and was able to fax the it to 131 of the researchers along with a response form. Here are the results from the 100 responses she received:

The statement reads as follows:

“The Meaning and Measurement of Intelligence

1. Intelligence is a very general mental capability that, among other things, involves the ability to reason, plan, solve problems, think abstractly, comprehend complex ideas, learn quickly and learn from experience. It is

not merely book learning, a narrow academic skill, or test-taking smarts. Rather, it reflects a broader and deeper capability for comprehending our surroundings—’catching on,’ ‘ making sense’ of things, or ‘figuring out’ what to do.

2. Intelligence, so defined, can be measured, and intelligence tests measure it well. They are among the most accurate (in technical terms, reliable and valid) of all psychological tests and assessments. They do not measure creativity, character, personality, or other important differences among individuals, nor are they intended to.3. While there are different types of intelligence tests, they all measure the same intelligence. Some use words or numbers and require specific cultural knowledge (like vocabulary). Other do not, and instead use shapes or designs and require knowledge of only simple, universal concepts (many/few, open/closed, up/down).

4. The spread of people along the IQ continuum, from low to high, can be. represented well by the bell curve (in statistical jargon, the “normal curve”). Most people cluster around the average (IQ 100). Few are either very bright or very dull: About 3% of Americans score above IQ 130 (often considered

the threshold for “giftedness”), with about the same percentage below IQ 70 (IQ 70-75 often being considered the threshold for

mental retardation).

5. Intelligence tests are not culturally biased against American blacks or other native-born, English-speaking peoples in the U.S. Rather, IQ scores predict equally accurately for all such Americans, regardless of race and social class. Individuals who do not understand English well can be given either a nonverbal test or one in their native language.

6. The brain processes underlying intelligence are still little understood. Current research looks, for example, at speed of neural transmission, glucose (energy) uptake, and electrical activity of the brain.

Group Differences

7. Members of all racial-ethnic groups can be found at every IQ level. The bell curves of different groups overlap considerably, but groups often differ in where their members tend to cluster along the IQ line. The bell curves for some groups (Jews and East Asians) are centered somewhat higher than for whites in general. Other groups (blacks and Hispanics) are centered somewhat lower than non-Hispanic whites.

8. The bell curve for whites is centered roughly around IQ 100; the bell curve for American blacks roughly around 85; and those for different subgroups of Hispanics roughly midway between those for whites and blacks. The evidence is less definitive for exactly where above IQ 100 the bell curves for Jews and Asians are centered.

Practical Importance

9. IQ is strongly related, probably more so than any other single measurable human trait, to many important educational, occupational, economic, and social outcomes. Its relation to the welfare and performance of individuals is very strong in some arenas in life (education, military training), moderate but robust in others (social competence), and modest but consistent in others (law-abidingness). Whatever IQ tests measure, it is of great practical and social importance.

10. A high IQ is an advantage in life because virtually all activities require some reasoning and decision-making. Conversely, a low IQ is often a disadvantage, especially in disorganized environments. Of course, a high IQ no more guarantees success than a low IQ guarantees failure in life. There are many exceptions, but the odds for success in our society greatly favor individuals with higher IQs.

11. The practical advantages of having a higher IQ increase as life settings become more complex (novel, ambiguous, changing, unpredictable, or multifaceted). For example, a high IQ is generally necessary to perform well in highly complex or fluid jobs (the professions, management); it is a considerable advantage in moderately complex jobs (crafts, clerical and police work); but it provides less advantage in settings that require only routine decision making or simple problem solving (unskilled work).

12. Differences in intelligence certainly are not the only factor affecting performance in education, training, and highly complex jobs (no one claims they are), but intelligence is often the most important. When individuals have already been selected for high (or low) intelligence and so do not differ

as much in IQ, as in graduate school (or special education), other influences on performance loom larger in comparison.

13. Certain personality traits, special talents, aptitudes, physical capabilities, experience, and the like are important (sometimes essential) for successful performance in many jobs, but they have narrower (or unknown) applicability or “transferability” across tasks and settings compared with general intelligence. Some scholars choose to refer to these other human traits as other “intelligences.”

Source and Stability of Within-Group Differences

14. Individuals differ in intelligence due to differences in both their environments and genetic heritage. Heritability estimates range from 0.4 to 0.8 (on a scale from 0 to l), most thereby indicating that genetics plays a bigger role than does environment in creating IQ differences among individuals. (Heritability is the squared correlation of phenotype

with genotype.) If all environments were to become equal for everyone, heritability would rise to 100% because all remaining differences in IQ would necessarily be genetic in origin.

15. Members of the same family also tend to differ substantially in intelligence (by an average of about 12 IQ points) for both genetic and environmental reasons. They differ genetically because biological brothers and sisters share exactly half their genes with each parent and, on the average, only half with each other. They also differ in IQ because they experience different environments within the same family.

16. That IQ may be highly heritable does not mean that it is not affected by the environment. Individuals are not born with fixed, unchangeable levels of intelligence (no one claims they are). IQs do gradually stabilize during childhood, however, and generally change little thereafter.

17. Although the environment is important in creating IQ differences, we do not know yet how to manipulate it to raise low IQs permanently. Whether recent attempts show promise is still a matter of considerable scientific debate.

I8. Genetically caused differences are not necessarily irremediable (consider diabetes, poor vision, and phenylketonuria), nor are environmentally caused ones necessarily remediable (consider injuries, poisons, severe neglect, and some diseases). Both may be preventable to some extent.

Source and Stability of Between-Group Differences

19. There is no persuasive evidence that the IQ bell curves for different racial-ethnic groups are converging. Surveys in some years show that gaps in academic achievement have narrowed a bit for some races, ages, school subjects and skill levels, but this picture seems too mixed to reflect a general shift in IQ levels themselves.

20. Racial-ethnic differences in IQ bell curves are essentially the same when youngsters leave high school as when they enter first grade. However, because bright youngsters learn faster than slow learners, these same IQ differences lead to growing disparities in amount learned as youngsters pro-

gress from grades one to 12. As large national surveys continue to show, black 17-year-olds perform, on the average, more like white 13-year-olds in reading, math, and science, with Hispanics in between.

21. The reasons that blacks differ among themselves in intelligence appear to be basically the same as those for why whites (or Asians or Hispanics) differ among themselves. Both environment and genetic heredity are involved.

22. There is no definitive answer to why IQ bell curves differ across racial-ethnic groups. The reasons for these IQ differences between groups may be markedly different from the reasons for why individuals differ among themselves within any particular group (whites or blacks or Asians). In fact, it

is wrong to assume, as many do, that the reason why some individuals in a population have high IQs but others have low IQs must be the same reason why some populations contain more such high (or low) IQ individuals than

others. Most experts believe that environment is important in pushing the bell curves apart, but that genetics could be involved too.

23. Racial-ethnic differences are somewhat smaller but still substantial for individuals from the same socioeconomic backgrounds. To illustrate, black students from prosperous families tend to score higher in IQ than blacks

from poor families, but they score no higher, on average, than whites from poor families.

24. Almost all Americans who identify themselves as black have white ancestors—the white admixture is about 20%, on average—and many self-designated whites, Hispanics, and others likewise have mixed ancestry. Because research on intelligence relies on self-classification into distinct racial categories, as does most other social-science research, its findings likewise relate to some unclear mixture of social and biological distinctions among groups (no one claims otherwise).

Implications for Social Policy

25. The research findings neither dictate nor preclude any particular social policy, because they can never determine our goals. They can, however, help us estimate the likely success and side-effects of pursuing those goals via different means.

Around the same period, the Board of Scientific Affairs of the American Psychological Association marshalled an 11-member taskforce to create its own statement [9] responding to The Bell Curve. The statement is much less concise than Gottfredson’s so as to make it unwieldy to quote in full again; it seems to push in the other direction regarding various issues pertinent to Hereditarians, but as Gottfredson notes [6], “(Three of the task force members were also signers of the “Mainstream” statement.)…It too concludes, for example, that differences in intelligence exist, can be measured fairly, are partly genetic (within races), and influence life outcomes.”

An even earlier (1986) such exercise to survey the views of the field comes from Sternberg’s 150-page book What Is Intelligence? Contemporary Viewpoints on Its Nature and Definition [10]. In it, he gives space for a variety of 25 eminent authors from various disciplines to detail their own views on the subject. Again, it’s much too long to cover here, but readers can easily imagine what might be in such a book containing submissions from everybody from Gardner and Sternberg to Carrol and Jensen.

Our earliest actual survey is the one done by Snyderman & Rothman in 1987 [11]. They followed three primary considerations in defining their population of experts to be sampled:

“First, the population should be neither so broad as to contain a large proportion of individuals with little or no experience with intelligence testing

nor so narrow as to include only those who might be considered to have a vested interest in testing.”“Second, we wished to include individuals with a variety of perspectives on the problem, including those who might have expertise on only a small part of the controversy.”

“The final criterion was that the population, and the sample drawn therefrom, be weighted in favor of those with the most expertise, as indicated by research and publications on issues dealing with testing. Therefore, only scholarly organizations were sampled….For those organizations where it was possible to separate PhD from non-PhD members, only members with doctorates were sampled.

The sample composition was as follows:

If you’re wondering what the “Primary” and “Secondary” groups are, you can disregard the secondary groups, as their responses did not differ from those of the primary groups to a statistically significant degree. The idea of the distinction was to separate out those who may have special expertise on specific questions while being otherwise ignorant about the larger field.

53% of primary experts either somewhat or strongly agreed that there was some sort of consensus as to the kinds of behaviors that are labeled “intelligence”, and 58% favored some sort of general intelligence in the factor structure of IQ subtests. Respondents however felt that there were certain aspects of intelligence not adequately measured by the tests:

Of those who felt qualified to answer, 94% of respondents thought there was evidence for a non-zero general heritability of IQ. However, a plurality (40% vs 39%) felt that there was insufficient evidence to provide a specific heritability estimate within Whites; of the 214 who gave an estimate, the mean response was a 59.6% heritability (SD = 16.6%).

Overall, compared to the later samples, this earlier sample of experts seems to be less hereditarian, more skeptical, less likely to think that there was sufficient evidence to answer various questions, and less endorsing of g theory.

The Validity Of Race:

There has been a recent trend among anthropologists against recognizing the validity of the concept of race.

The most recent survey of anthropologists asking about this issue was published in 2016 [11]. The sample focused on members of the American Anthropological Association (AAA), with 42,231 members’ email addresses scraped from Outwit Hub, and the resulting communications generating 3,286 responses. Certain items in the survey were modeled off of a previous survey [12] published in 1978 so as to better facilitate direct temporal comparisons; for this reason, 1,368 student responses were cut so as to better resemble the 1978 sample. Results then are based on the remaining 1918 responses. Here are the resulting shifts among the two reported items:

As he explains [13], Lieberman actually conducted three such previous surveys of the AAA. In his first 1978 survey [12], 37% (138 of 374) of the respondents agreed with the statement that “Races do not exist because isolation of groups has been infrequent, populations have always interbred.” In the next 1983-1984 survey [14], 41% (148 of 364) of the responding physical anthropologists disagreed with the statement that "There are biological races in the species Homo sapiens." Finally, in the 1999 survey [15], 69% (191 of 290) disagreed with the same statement.

Region:

This sort of race denial, however, is limited primarily to western Europe and to the Anglosphere. The countries with the greatest tendency to accept the concept of race are the former Soviet countries, with the third world being split between the two.

The Anglosphere:

The 1999 AAA survey [15] questionnaire was also sent to sent to a few other English speaking nations [13], with 7 in 10 respondents from Great Britain rejecting the concept, and 72% (33 of 46) respondents from Canada rejecting the concept.

Europe:

In 2002 [17], 120 members of the European Anthropological Association were polled on their views of race, with with the survey drawing 60 responses from 18 European nations. Specifically, the two questions were as follows:

Q1: Do you agree with the statement: “There are biological races (meaning subspecies) within the species Homo sapiens”?

Q2: Do you support race in any other of its meanings (i.e., do you believe that human races exist)?

The responses were as follows:

As we can see, former Eastern-Bloc countries were substantially less likely to disagree with the validity of the concept (30%) than were the Western-Bloc countries (65%). In Poland specifically, we also have a couple more such surveys. In the first 1999 polling of the Polish Anthropological Society (PAS) conducted in 1999 [18], the 55 responses were collected specifying agreement or disagreement with the statement that “There are biological races (meaning subspecies) within the species Homo sapiens.” Of these, 31% agreed with this subspecies definition of race. The author however suspected that this subspecies definition was too strict, and did follow-up polling in the 2001 meeting where four different definitions of race were given to choose from, with the subspecies definition being merely one of the four; this time, 75% agreed to at least one of the four definitions [19].

The Spanish World:

At the same time as the 1999 AAA survey [15], another survey [16] was sent to 150 specialists in the Spanish-speaking world; as described second-hand [13, p.908-9], of the 40 responses from the seven Latin American nations (Argentina, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Venezuela, Brazil, Guadalupe, & Mexico), 20 accepted the concept of race, 18 rejected it, and 2 were neutral. Of these however, the Cuban respondents were disproportionately more likely to accept the concept than were those from the other 7 countries. All 10 respondents in the sample that were from Spain, along with all 14 respondents from the USA, again rejected the concept.

China:

We don’t have any actual polling of experts in China, but we do have one paper [20] which looked at 779 articles in Acta Anthropologica Sinica, China’s only biological anthropological journal. The authors describe their results as follows:

“When we applied Cartmill’s approach to the Chinese sample we found that all of the articles used the race concept and none of them questioned its value. Since these active researchers are also members of the teaching staffs at various educational institutions, it is very likely that this attitude will be transmitted to the next generation of Chinese scientists.”

Expertise:

For Western Europe and the Anglosphere then, we might ask the question: “Why does expert opinion here differ so heavily from the rest of the world?” Do we have access to research which is better in some way? Are we somehow better informed? If so, we would expect the higher-quality anthropologists to reject the concept. Instead, we see the opposite:

Anthropologists differ in the relevancy of their expertise to the question of the biological validity of the concept of race. Physical anthropology (or biological anthropology) in the most prescient subdiscipline, as it is the one concerned with Human diversity, evolution, and origin. As such, the most recent survey [11] analyzed how physical anthropologists differed in their responses from the other subdisciplines of anthropology. The authors also came up with a measure of familiarity with genetic ancestry testing which they describe as follows:

“Given the academic and public discourses on genetic ancestry testing and concerns about its potential reification of race, a separate analysis was performed to determine whether familiarity with genetic ancestry testing (i.e., a combined testing item that is the sum of the three items—having obtained a genetic ancestry test, interest in getting one, or used genetic ancestry inference in research—with possible scores 0, 1, 2, and 3) was correlated with levels of agreement with the statements about race.”

Here are a few results the authors highlight as to their association with various levels of expertise. As we can see, for 3/4 comparisons, the better anthropologists held views of greater racial essentialism:

Worth pointing out however is that for the comparisons between ‘experienced’ and ‘non-experienced’ anthropologists, any score other than zero is given the same value as somebody who has actually used genetic ancestry testing in their research at some point. If, instead, we look at the correlation coefficients reported in table 2, we can see that the direction of the effect flips, and those agreeing with the statement that “No races exist now or ever did” suddenly becomes negatively correlated with greater experience with genetic ancestry testing:

Of the 43 statements with a statistically-significant association between experience and responses, excluding 7 statements which don’t seem to clearly have anything to do with racial essentialism (These are the 9th & 10th statements on science; the 5th and 6th statements on medicine; and the 4th, 5th, & 6th statements on social & societal issues) to bring the total down to 37, greater experience with genetic ancestry testing was associated with greater racial essentialism on 34 of the statements.

NOTE: Even for two of the items (the 12th & 13th statements on social & societal issues, which really just ask the same thing in two different ways) that I counted as negative correlations between essentialism and experience, I was being generous in doing so in that my rationale for doing so was that a belief in racial essentialism should correspond with the belief that exposure to evidence would increase racial essentialism in others. It’s fully possible however that these two items should be counted the other way under the rationale that the experienced experts want genetic ancestry testing to be seen as non-racist so that it doesn’t get banned. After all, they already expressed such a desire by disagreeing with statement 7.

As for the 10 statements without a statistically-significant association between expertise and responses, excluding 2 statements which don’t seem to clearly have anything to do with racial essentialism (These are the 10th statement on science, and the 6th statement on social & societal issues) to bring the total down to 8, greater experience with genetic ancestry testing was associated with greater racial essentialism on 4 of the statements.

Notably however, on the 19th statement on science, I would actually disagree with the experts in their insignificantly-greater racial essentialism, though explaining why they’re wrong is beyond current scope.

Reinforcing the findings on agreement by subdiscipline, Lieberman again found physical anthropologists to be more likely to agree that “There are biological races in the species Homo sapiens” than were cultural anthropologists [14 & 15]:

Lieberman also found something interesting in a 1983-1984 survey of animal behavior biologists, which he compares to the physical anthropologists of the same year [21]:

Although there was no obvious consistent trend as to the effect of additional degrees of education in either field, the animal behavior biologists were substantially more likely than the physical anthropologists to agree that biological races exist within Humans. This speaks to the issue that when only dealing with Humans, we can always hold the races of man to unreasonably-high requirements for differentiation, while if we also deal other animals, then we’re forced to acknowledge that any standards which would disqualify the races of man would also disqualify the subspecies of various other animals. A good exercise in a future survey would be to present the experts with various genetic statistics regarding things like heterozygosity, fixation index, clusteredness, and clinal discontinuity as they apply to the Human races and to the subspecies of various other animals without labelling what species the groups actually belong to.

Finally, the survey of the European Anthropological Association [17] was an outlier in that in both Eastern and Western Europe, but especially in Eastern Europe, rejection of the concept of race was higher among the physical anthropologists as well as the anthropologists with more advanced degrees. Ironically enough, if each region were to really ‘just follow the science’, then it seems that we’d actually trade places in terms of who believes what.

Privilege:

Both the most recent [11] survey and the least recent [12] survey of the American Anthropological Association investigate the possibility of racial essentialism being mediated by the demographics of the anthropologists. Indeed, the most recent [11] finds White anthropologists of both sexes to be especially likely to endorse racial essentialism, and finds male anthropologists of all races to be more likely to endorse racial essentialism. The oldest survey [12] also compared first-born White Anglo-Saxon protestant (WASP) male anthropologists who were born in the United States to the anthropologists with any characteristic that could disqualify them from that group; again, the first-born WASP men gave more racially essentialist responses.

The accusation can then be made that racial essentialism is just motivated by WASP men wanting to defend their privilege and that those lacking these privileges are the unbiased group whose views reflect their neutrality. However, the counter accusation can just as easily be made that racial constructivist views are motivated by the desire to justify europhobic, ethnomarxist, redistribution efforts inspired by envy, with the WASP men being the unbiased group who lack this motivation and whose views reflect their greater neutrality.

As a tiebreaker then, we can offer the alternative hypothesis that these differences in racial essentialism can be explained by the higher general mental ability and rationality of Whites [22] and of men [23 & 24, table 13.11].

Race & Intelligence:

The earliest known survey of contemporary researchers’ views on the innateness of the Black-White IQ gap was published in 1968 [25]. The authors reviewed the literature at the time [mainly 26, 27, 28, & 29] to come up with a list of 128 authors of relevant research as they defined it. They found mailing addresses for 104 of them, from whom they received 82 completed questionaires. For those that they could not get a response from, the two survey authors rated what they expected the researchers responses might be given the texts of the research they had produced. Despite being under conditions of semi-blind reviewing conditions while doing so, and despite differeing in the degree of blinding, the two survey authors’ ratings correlated at r = +0.94, thereby supporting the validity of their ratings. The researchers views were categorized as follows:

Notably, contrary to the view that racism has declined with time as the evidence has come in, the experts seem to have had much more environmentalist views of the gaps back in the day than they are commonly imagined to have had. Depending on whether we are to accept the authors’ ratings of the non-respondents, the percent of researchers who thought there to be at least “an indication of innate Negro inferiority” was either 11.7%, or 13.4% (11.7% in the case of acceptance). The questionaires that were sent also collected various demographic data, which related to the researchers views as follows:

As we can see, those with more hereditarian views of the causes of the IQ gap published their research at younger ages, were more likely to be first-born children, had fewer foreign-born grandparents, had higher class rankings, had more educated parents, and were more likely to grow up in the suburbs instead of the cities.

Our next survey was conducted in 1970 [30], when 526 members of the American Psychological Association was asked to rate their agreement with Arthur Jensen’s famous quote that “It is a not unreasonable hypothesis that genetic factors are strongly implicated in the average Negro-white intelligence difference. The preponderance of the evidence is, in my opinion, less consistent with a strictly environmental hypothesis than with a genetic hypothesis.” The results were as follows:

“Other” category simply sent the card back blank with a statement indicating that they could not choose among the six categories

Some demographic information was collected, and APA members from the deep South were especially likely to agree while Jews were especially likely to disagree:

The Snyderman and Rothman survey from earlier [11] also asked their sample to submit their views regarding the source of the Black-White IQ gap. The responses were as follows:

As we can see, compared to the 1968 survey [25], the percentage of respondents who viewed genes as having at least something to do with the picture had clearly grown a substantial amount.

The most recent (2020; data collected in 2013) expert opinion paper on IQ [2] also asked respondents to submit specific between-group heritability estimates for the Black-White IQ gap. Again, the growth is stark:

Over 80% thought that genes have at least something to do with the gap, over 5% thought the gap to be 100% genetic, 40% thought the gap to be more environmental than genetic, 43% thought the gap to be more genetic than environmental, 17% thought the gap to be evenly environmental and genetic, and the mean heritability estimate was 49%.

This 2019 paper [38] surveyed a list of 1,632 anthropologists in all doctoral

anthropology programs in the United States via the American Anthropological Association 2013–2014 AnthroGuide. 301 usable surveys were received, and of the 273 who responded to the question, 14% agreed that “the comparatively high IQ scores and disproportionate scientific contributions of Ashkenazi Jews … reflect in part a genetic component of their intelligence” while 57% disagreed.This 2017 paper [34] surveyed members of the Society of Experimental Social Psychology in 2015; the response rate was 37%, yielding 335 participants. Respondents were asked “how likely they thought it was that members of some ethnic groups were genetically more intelligent” than members of other ethnic groups, and the average response was 26.4% [34, p.18]. This is impressive considering how irrelevant the specialization is to the question, and how much softer of a field social psychology is than cognitive psychology and differential psychology. To recap, social psychology has an estimated replication rate of 25% [35], cognitive psychology has an estimated replication rate of 50% [35], and differential psychology has an estimated replication rate of 87% [36].

Other:

The 2020 expert opinion paper on IQ [2] was actually conducted in 2013 [31]; the various analyses were just conducted and published afterwards. The authors actually published two more which covered over other topics [32 & 33] about the causes of the national IQ gaps and the FLynn effect respectively. The findings are mostly conveyed in text, and both papers are already pretty short as is, so discussing them here would just be regurgitation.

We have a brand-new (12/01/2022; 5 days ago as of writing) survey of evolutionary psychologists [37] asked to give their views on Human psychology and behavior. The authors describe their recruitment procedures as follows:

“E-mail invitations were sent to 1) participants in the first wave of the Survey of Evolutionary Scholars who agreed to participate in future research and provided an e-mail address; 2) The membership of the International Society for Human Ethology; 3) The membership of the Northeastern Evolutionary Psychology Society and other individuals listed in conference programs (2008–2019); 4) individuals listed in conference programs of the Human Behavior and Evolution Society (2014–2019). E-mail invitations were sent on 31 July 2020 with reminders for those who had not completed surveys on 8 November and 22 November 2020. Officers for the European Human Behavior and Evolution Association and the Polish Society for Human and Evolution Studies distributed invitations to participate to the societies’ contact lists. Responses that were >70% complete were retained for analyses.”

The findings are rather interesting:

As we can see, 93% believe in individual psychological differences arising from genetics to some degree, about half support Phillip Rushton’s r/K selection theory, and ~2/5 believe that group selection was of substantial importance to Human evolution.

Sauce:

Carroll, J. B. (1993). Human cognitive abilities: A survey of factor-analytic studies (No. 1). Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from https://not-equal.org/Sources/Source140-Carroll1993.pdf

Rindermann, H., Becker, D., & Coyle, T. R. (2020). Survey of expert opinion on intelligence: Intelligence research, experts' background, controversial issues, and the media. Intelligence, 78, 101406. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2019.101406

Spearman, C. M., Quigley, M. J., Quigley, M. R., & Wilberger, J. E. (2010). Survey of the h index for all of academic neurosurgery: another power-law phenomenon?. Journal of neurosurgery, 113(5), 929-933. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.3171/2010.4.JNS091842

Last, Sean. (2020). On Trusting Academic Experts. Ideas And Data. Retrieved from https://ideasanddata.wordpress.com/2020/06/25/on-trusting-academic-experts/

Kirkegaard, E. O. W. K. (2020). Against trust in neuroscience. Clear Language, Clear Mind. Retrieved from https://emilkirkegaard.dk/en/2020/08/against-trust-in-neuroscience/

Gottfredson, L. S. (1997). Mainstream science on intelligence: An editorial with 52 signatories, history, and bibliography. Intelligence, 24(1), 13-23. Retrieved from https://www1.udel.edu/educ/gottfredson/reprints/1997mainstream.pdf

Reeve, C. L., & Charles, J. E. (2008). Survey of opinions on the primacy of g and social consequences of ability testing: A comparison of expert and non-expert views. Intelligence, 36(6), 681-688. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2008.03.007

Murphy, K. R., Cronin, B. E., & Tam, A. P. (2003). Controversy and consensus regarding the use of cognitive ability testing in organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(4), 660. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.4.660

Neisser, U., Boodoo, G., Bouchard Jr, T. J., Boykin, A. W., Brody, N., Ceci, S. J., ... & Urbina, S. (1996). Intelligence: knowns and unknowns. American psychologist, 51(2), 77. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.51.2.77

Sternberg, R. J., & Detterman, D. K. (1986). What Is Intelligence?: Contemporary viewpoints on its nature and definition. Ablex Publishing Corporation. Retrieved from https://b-ok.cc/book/3511014/ec9678

Wagner, J. K., Yu, J. H., Ifekwunigwe, J. O., Harrell, T. M., Bamshad, M. J., & Royal, C. D. (2017). Anthropologists' views on race, ancestry, and genetics. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 162(2), 318-327. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.23120

Lieberman, L., & Reynolds, L. T. (1978). The debate over race revisited: An empirical investigation. Phylon (1960-), 39(4), 333-343. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.2307/274899

Lieberman, L., Kaszycka, K. A., Martinez, A. J., Yablonsky, F. L., Kirk, R. C., Štrkalj, G., ... & Sun, L. (2004). The race concept in six regions: variation without consensus. Collegium antropologicum, 28(2), 907-921. Retrieved from https://hrcak.srce.hr/file/8770

Lieberman, L., Stevenson, B. W., & Reynolds, L. T. (1989). Race and anthropology: A core concept without consensus. Anthropology & education quarterly, 20(2), 67-73. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1525/aeq.1989.20.2.05x0840h

Lieberman, L., Kirk, R. C., & Littlefield, A. (2003). Perishing paradigm: race—1931–99. American Anthropologist, 105(1), 110-113. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.2003.105.1.110

Martínez Fuentes, A.J. (2000). El concepto de raza: ser o no ser. VI Congreso de la Asociación Latinoamericana de Antropología Biológica. Maldonado, Uruguay. As cited in Fuentes, A. J. M., & Montané, M. A. El status del concepto de raza en la Antropología biológica contemporánea.

Kaszycka, K. A., Štrkalj, G., & Strzałko, J. (2009). Current views of European anthropologists on race: Influence of educational and ideological background. American Anthropologist, 111(1), 43-56. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1433.2009.01076.x

Kaszycka, K., & trkalj, G. (2002). Anthropologists’ attitudes towards the concept of race: The Polish sample. Current Anthropology, 43(2), 329-335. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1086/339381

Kaszycka, K. A., & Strzałko, J. (2003). Race: Tradition and convenience, or taxonomic reality? More on the race concept in Polish anthropology. Anthropological Review, 66, 23-37. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Katarzyna-Kaszycka/publication/255730272_Race_Tradition_and_Convenience_or_Taxonomic_Reality_More_on_the_Race_Concept_in_Polish_Anthropology/links/0c960520a0508375f7000000/Race-Tradition-and-Convenience-or-Taxonomic-Reality-More-on-the-Race-Concept-in-Polish-Anthropology.pdf

Wang, Q., trkalj, G., & Sun, L. (2003). On the concept of race in Chinese biological anthropology: alive and well. Current Anthropology, 44(3), 403-403. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1086/374899

Lieberman, L., Hampton, R. E., Littlefield, A., & Hallead, G. (1992). Race in biology and anthropology: A study of college texts and professors. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 29(3), 301-321. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.3660290308

Roth, P. L., Bevier, C. A., Bobko, P., SWITZER III, F. S., & Tyler, P. (2001). Ethnic group differences in cognitive ability in employment and educational settings: A meta‐analysis. Personnel Psychology, 54(2), 297-330. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2001.tb00094.x

Lynn, R. (2017). Sex differences in intelligence: The developmental theory. Mankind Quarterly, 58(1). Retrieved from https://not-equal.org/content/pdf/misc/10.46469mq.2017.58.1.2.pdf

Stanovich, K. E., West, R. F., & Toplak, M. E. (2016). The rationality quotient: Toward a test of rational thinking. MIT press. Retrieved from https://not-equal.org/Sources/Source376-Stanovich2016.pdf

Sherwood, J. J., & Nataupsky, M. (1968). Predicting the conclusions of Negro—White intelligence research from biographical characteristics of the investigator. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 8(1p1), 53. Retrieved from https://not-equal.org/content/pdf/misc/Sherwood&Nataupsky(1968).pdf

Dreger, R. M., & Miller, K. S. (1960). Comparative psychological studies of Negroes and whites in the United States. Psychological Bulletin, 57(5), 361. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1037/h0047639

Dreger, R. M., & Miller, K. S. (1965, April). Recent research in psychological comparisons of Negroes and whites in the United States. In meeting of the Southeastern Psychological Association, Atlanta. As cited in Sherwood, J. J., & Nataupsky, M. (1968). Predicting the conclusions of Negro—White intelligence research from biographical characteristics of the investigator. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 8(1p1), 53.

Klineberg, O. (1963). Negro-white differences in intelligence test performance: A new look at an old problem. American Psychologist, 18(4), 198. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1037/h0041515

Shuey, A. M. (1958). The testing of Negro intelligence. Retrieved from https://not-equal.org/Sources/Source775-Shuey1966.pdf

Friedrichs, R. W. (1973). The impact of social factors upon scientific judgment: The" Jensen Thesis" as appraised by members of the American Psychological Association. The Journal of Negro Education, 42(4), 429-438. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.2307/2966555

Rindermann, H., Coyle, T. R., & Becker, D. 2013 survey of expert opinion on intelligence. Retrieved from https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=fa28a21a36e57ac8bc18470e059ad1de369ca255

Rindermann, H., Becker, D., & Coyle, T. R. (2016). Survey of expert opinion on intelligence: Causes of international differences in cognitive ability tests. Frontiers in psychology, 7, 399. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00399

Rindermann, H., Becker, D., & Coyle, T. R. (2017). Survey of expert opinion on intelligence: The FLynn effect and the future of intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences, 106, 242-247. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.10.061

von Hippel, W., & Buss, D. M. (2017). Do Ideologically Driven Scientific Agendas Impede the Understanding and Acceptance of Evolutionary Principles in Social Psychology?. In The Politics of Social Psychology (pp. 5-25). Psychology Press. Retrieved from https://labs.la.utexas.edu/buss/files/2013/02/von-Hippel-and-Buss-2017.pdf

Open Science Collaboration. (2015). Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science, 349(6251), aac4716. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aac4716

Soto, C. J. (2019). How replicable are links between personality traits and consequential life outcomes? The life outcomes of personality replication project. Psychological Science, 30(5), 711-727. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797619831612

Kruger, D. J., Fisher, M. L., & Salmon, C. (2022). What do evolutionary researchers believe about human psychology and behavior?. Evolution and Human Behavior. Retrieved from https://not-equal.org/content/pdf/misc/Kruger2022.pdf

Horowitz, M., Yaworsky, W., & Kickham, K. (2019). Anthropology’s science wars: Insights from a new survey. Current Anthropology, 60(5), 674-698. Retrieved from https://sci-hub.ru/https://doi.org/10.1086/705409

I love how this extremely technical, sober and scientific article concludes with the most trollish and racist meme ever lmao

To be fair, US Blacks have higher PISA points than many non-black countries.(inluding some european countries). Perhaps we should say there are differences based on natural selection rather than racial.

https://www.unz.com/isteve/the-new-2018-pisa-school-test-scores-usa-usa/